CFEngine is agent based software. It resides on and runs processes on each individual computer under its management. That means you do not need to grant any security credentials for login to CFEngine. Instead, for normal operation, CFEngine runs in privileged `root' or `Administrator' mode to get access to system resources and makes these available safely to authorized enquiries.

A CFEngine installation is thus required on every machine you want to manage: client and server, desktop or blade. Typically, you will single out one machine to be a policy server or hub. In very large networks of many thousands of machines, you might need several policy servers, i.e. several hubs.

Any piece of software has two different architectures, which should not be confused:

Information flow is about how users determine what promises the software should keep; this is entirely informational and once decisions are made they can be stored (cached) for an indefinite time. The dependence graph explains what services or resources are required by the software in order to keep its promises. This is a strong dependency because the software is unable to function without the availability of these resources at all times. Systems are robust if they are only weakly coupled. Strong dependence introduced fragility of design.

In many software products these two separate models are identical in design and implementation. However, Promise Theory maintains their independence and CFEngine makes no assumptions about the kind of information flows that should be set up.

| CFEngine takes host autonomy as its guiding architectural principle. Agents are functionally independent of one another and only weak couplings can be promised. |

The implication of this principle is that CFEngine is robust to failures of communication (e.g. network connectivity) and that each host is responsible for maintaining its own state. This affects the security and scalability of the solution.

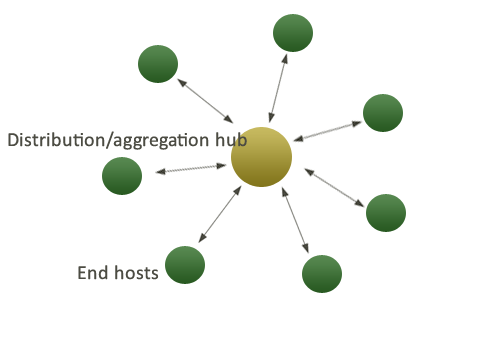

The default CFEngine Nova architecture uses a single hub or policy server to publish changes of policy and to aggregate knowledge about the environment, but you can set up as many as you like to manage different parts of your organization independently. The CFEngine technology is not centralized by nature. Most users choose to centralize updating of policy and report aggregation for convenience however.

If you operate CFEngine Nova in its default mode, the hub acts as a server from which every other client machine can access policy updates. It also acts as a collector, aggregating summary information from each machine and weaving it into a knowledge map about the datacenter.

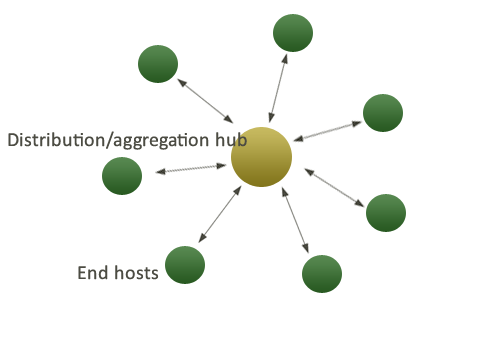

For a single hub configuration, the figure below shows a normal process approach to managing policy. Policy is edited and developed at a Policy Definition Point, outside of normal production environment. This can be done using the specialized editor embedded in CFEngine Nova, or it can be done using any text editor of your choice.

Edits are made in conjunction with a version control repository1, which should be used to document the reasons for changes to policy2. When a change has been tested and approved, it will be copied manually to the policy dispatch point on one or more distribution servers. All other machines will then download policy updates from that single location according to their own schedule.

If an agent receives a policy proposal that is badly formed or in some way non-executable, it switches to a failover strategy to recover. It will continue in this mode until a new policy proposal is available that can be executed.

The CFEngine agent clones itself to avoid limitations of operating systems like Windows, where programs and disk files cannot be altered while in use. When new software updates are available, CFEngine can update itself from a suitable source, and restart its own services. Should the new version be corrupt, the twin will still be the old working version, hence the software will be able to recover as soon as a new valid version is available.

Each agent runs independently of others, unless it promises to acquire services from other hosts. Thus all processing capacity and decision-making computation takes place on the end nodes of the communication graph. There is no apriori need for agents to collect data from any source outside themselves, though this is a highly convenient strategy. CFEngine's use of the network may be called opportunistic.

Each agent is the ultimate arbiter of whether or not to accept information from external sources. This makes CFEngine ideal for use in federated architectures, where attention to local requirements is paramount for whatever reason. Federation is typically a recommended strategy when the cost of avoiding local specialization outweighs the price of having local policy-makers. Universities and large companies (e.g. formed through acquisition) are typical candidates for federated management. Federation is facilitated by an essentially `service oriented architecture'3, i.e. a weak coupling.

The concept of security, while various in its interpretation and intented use, is related to a feeling of safety. No system is completely safe from every threat, thus no system can promise complete security. Security is ultimately defined by a model, an attitude, and a policy. It involves a set of compromises called a trust model that determines where you draw the line in the sand between trusted and risky.

CFEngine adheres to the following design principles:

CFEngine uses a simple, private protocol that is based on (but not identical to) that used by OpenSSH (the free version of the Secure Shel). It is based on mutual, bi-directional challenge-reponse using an autonomous Public Key Infrastructure.

The right to connect to the server is the first line of defence. CFEngine has built into it the equivalent of the `TCP wrappers' software to deny non-authorized hosts the ability to connect to the server at all.

allowconnects

allowallconnects

denyconnects

maproot. If this is false, only resources owned by the authenticated user name may be transmitted.

ifencrypted is set, access is denied to non-encrypted connections.

CFEngine Community Edition uses RSA 2048 public key encryption for authentication. These are generated by the ‘cf-key’ command. It generates a 128 bit random Blowfish encryption key for data transmission. Challenge response is verified by an MD5 hash.

Commercial Editions of CFEngine use the same RSA 2048 key for authentication, and then AES 256 with a 256 bit random key for data transmission. The latter is validated for FIPS 140-2 government use in the United States of America. Challenge response is verified by a SHA256 hash.

The concept of voluntary cooperation used by CFEngine places restrictions on how files can be copied between hosts. CFEngine allows only `pull' (download) but not `push' (upload). Users cannot force an agent to perform an operation against local policy.

To allow remote copying between two systems each of the system must explicitly grant access before the operation can take place.

Authentication is about making sure users are who they say you are. Traditionally, there are two approaches: the trusted third party (arbiter of the truth) approach, and the challenge-response approach. The Trust Third Party decides whether two individuals who want to authenticate should trust each other. This is the model used in the Web.

The challenge-response approach allows each individual to decide personally whether to trust the other. This is the approach used by CFEngine. Its model is based in the Secure Shell (OpenSSH).

Two machines authenticate each other in a public key exchange

process. For key exchange between client and server, the server has to

decide if it will trust the client by using the trustkeysfrom

directive. The trustkeysfrom directive allows the server to accept

keys from one or more machines.

On the client-side the client also has to specify if it will trust key

from the server by using the trustkey directive. The trustkey

directive in copy_from allows a client to decide whether to

accept keys from a server. The CFEngine authentication model is based

on the ssh scheme, however unlike ssh, CFEngine

authentication is not interactive and the keys are generated by

cf-key program instead of ‘ssh key-gen’ program. Key

acceptance is accomplished in CFEngine using trust-key method. Once

the keys have been exchange the trust settings are irrelevant.

Buffer overflow attacks are extremely unlikely in CFEngine by design. The likelihood of a bug in CFEngine should be compared to the likelihood of a bug existing in the firewall itself.

Denial of Service attacks can be mitigated by careful

configuration. cf-serverd reads a fixed number of bytes from the

input stream before deciding whether to drop a connection from a

remote host, so it is not possible to buffer overflow attack before

rejection of an invalid host IP.

Another possibility is to use a standard VPN to the inside of the firewall. That way one is concerned first and foremost with the vulnerabilities of the VPN software.

The CFEngine security model, as well as the design of the server, disallows the uploading of information. No message sent over the CFEngine channel can alter data on the server. (This assumes that buffer overflows are impossible.)

Assuming that buffer overflow attacks and DOS attacks are highly improbable, the main worry with opening a port is that intruders will be able to gain access to unauthorized data. If the firewall is configured to open only connections from the policy mirror, then an attacker must spoof the IP of the policy attacker. This requires access to another host in the DMZ and is non-trivial. However, suppose the attacker succeeds then the worst he/she can do is to download information that is available to the policy-mirror. But that information is already available in the DMZ since the data have been exported as part of the policy, thus there is no breach of security. (Security must be understood to be a breach of the terms of policy that has been decided.)

If an attacker gains root access to the mirror, he/she will be able to affect the policy distributed to any host. The policy-mirror has no access to alter any information on the policy source host. Note that this is consistent with the firewall security model of trusted/untrusted regions. The firewall does not mitigate the responsibility of security every host in a network regardless of which side of the firewall it is connected.

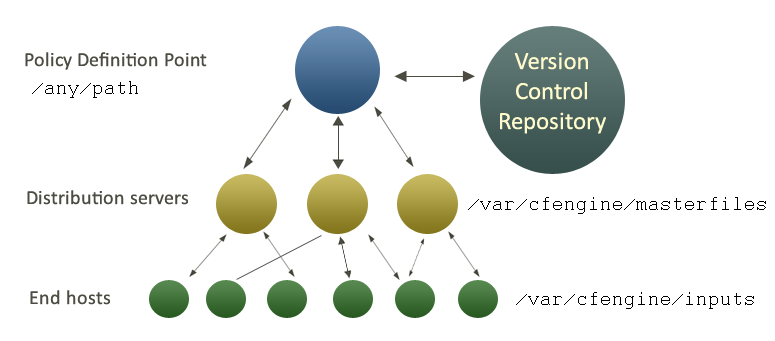

Some users want to use CFEngine's remote copying mechanism through a firewall, in particular to update the CFEngine policy on hosts inside a DMZ (so-called de-militarized zone). In making a risk assessment, it is important to see the firewall security model together with the CFEngine security model. CFEngine's security record is better than most firewalls, but Firewalls are nearly always trusted because they are `security products'.

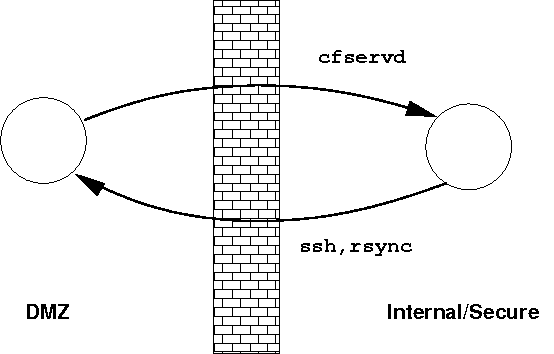

Any piece of software that traverses a firewall can, in principle, weaken the security of the barrier. On the other hand, a strong piece or software might have better security than the firewall itself. Consider the example in the figure;

We label the regions inside and outside of the firewall as the “secure area" and “Demilitarized Zone" for convenience. It should be understood that the areas inside a firewall is not necessarily secure in any sense of the word unless the firewall configuration is understood together with all other security measures.

Our problem is to copy files from the “secure” source machine to hosts in the DMZ, in order to send them their configuration policy updates. There are two ways of getting files through the firewall:

One of the

main aims of a firewall is to prevent hosts outside the secure area

from opening connections to hosts in the secure area. If we want

cfagent processes on the outside of the firewall to receive updated policies

from the inside of the firewall, information has to traverse the

firewall.

CFEngine's trust model is fundamentally at odds with the external firewall concept. CFEngine says: “I am my own boss. I don't trust anyone to push me data.” The firewall says: “I only trust things that are behind me.” The firewall thinks it is being secure if it pushes data from behind itself to the DMZ. CFEngine thinks it is being secure if it makes the decision to pull the data autonomously, without any orders from some potentially unknown machine. One of these mechanisms has to give if firewalls are to co-exist with CFEngine.

From the firewall's viewpoint, push and pull are different: a push requires only an outgoing connection from a trusted source to an untrusted destination; a pull necessarily requires an untrusted connection being opened to a trusted server within the secure area. For some firewall administrators, the latter is simply unacceptable (because they are conditioned to trust their firewall). But it is important to evaluate the actual risk. We have a few observations about the latter to offer at this point:

By creating a policy mirror in the DMZ, these issues can be worked around. This is the recommended way to copy files, so that normal CFEngine pull methods can then be used by all other hosts in the DMZ, using the mirror as their source. The policy mirror host should be as secure as possible, with preferably few or no other services running that might allow an attacker to compromise it. In this configuration, you are using the mirror host as an envoi of the secure region in the DMZ.

Any method of pushing a new version of policy can be chosen in principle: CVS, FTP, RSYNC, SCP. The security disadvantage of the push method is that it opens a port on the policy-mirror, and therefore the same vulnerability is now present on the mirror, except that now you have to trust the security of another piece of software too. Since this is not a CFEngine port, no guarantees can be made about what access attackers will get to the mirror host.

Suppose you are allowed to open a hole in your firewall to a single policy host on the inside. To distribute files to hosts that are outside the firewall it is only necessary to open a single tunnel through the firewall from the policy-mirror to the CFEngine service port on the source machine. Connections from any other host will still be denied by the firewall. This minimizes the risk of any problems caused by attackers.

To open a tunnel through the firewall, you need to alter the filter rules. A firewall blocks access at the network level. Configuring the opening of a single port is straightforward. We present some sample rules below, but make sure you seek the guidance of an expert if necessary.

Cisco IOS rules look like this

ip access-group 100 in

access-list 100 permit tcp mirror host source eq 5308

access-list 100 deny ip any any

Linux iptables rules might look something like this:

iptables -N newchain

iptables -A newchain -p tcp -s mirror-ip 5308 -j ACCEPT

iptables -A newchain -j DENY

Once a new copy of the policy is downloaded by CFEngine to the policy mirror, other clients in the DMZ can download that copy from the mirror. The security of other hosts in the DMZ is dependent on the security of the policy mirror.

Message digests are supposed to be unbreakable, tamperproof technologies, but of course everything can be broken by a sufficiently determined attacker. Suppose someone wanted to edit a file and alter the CFEngine checksum database to cover their tracks. If they had broken into your system, this is potentially easy to do. How can we detect whether this has happened or not?

A simple solution to this problem is to use another checksum-based operation to copy the database to a completely different host. By using a copy operation based on a checksum value, we can also remotely detect a change in the checksum database itself.

Consider the following code:

bundle agent change_management

{

vars:

"watch_files" slist => {

"/etc/passwd",

"/etc/shadow",

"/etc/group",

"/etc/services"

};

"neighbours" slist => peers("/var/cfengine/inputs/hostlist","#.*",4),

comment => "Partition the network into groups";

files:

"$(watch_files)"

comment => "Change detection on the above",

changes => detect_diff_content;

#######################################################################

# Redundant cross monitoring .......................................

#######################################################################

"$(sys.workdir)/nw/$(neighbours)_checksum_digests.db"

comment => "Watching our peers remote hash tables for changes - cross check",

copy_from => remote_cp("$(sys.workdir)/checksum_digests.db","$(neighbours)"),

depends_on => { "grant_hash_tables" },

action => neighbourwatch("File changes observed on $(neighbours)");

It works by building a list of neighbours for each host. The function

peers can be used for this. Using a file which contains a list

of all hosts running CFEngine, we create a list of hosts to copy

databases . Each host in the network therefore takes on the

responsibility to watch over its neighbours.

In theory, all four neighbours should signal this change. If an attacker had detailed knowledge of the system, he or she might be able to subvert one or two of these before the change was detected, but it is unlikely that all four could be covered up. At any rate, this approach maximizes the chances of change detection.

Consider what happens if an attacker changes a file an edits the checksum database. Each of the four hosts that has been designated a neighbour will attempt to update their own copy of the database. If the database has been tampered with, they will detect a change in the checksums of the remote copy versus the original. The file will therefore be copied.

It is not a big problem that others have a copy of your checksum database. They cannot see the contents of your files from this. A possibly greater problem is that this configuration will unleash an avalanche of messages if a change is detected. This makes messages visible at least.

[1] CFEngine supports integration with Subversion through its Mission Portal, but any versioning system can of course be used.

[2] CFEngine and version control will document what the changes are, but what is usually missing from user documentation is an explanation of the reasonsing behind the change. This is most valuable when trying to diagnose and debug changes later.

[3] NB. CFEngine does not use web services as part of its technology, so this should not be construed to mean SOA.