Modularizing and Orchestrating System Policy

Orchestration

COMPLETE TABLE OF CONTENTS

Summary of contents

What is modularity?

Modularity is the ability to separate concerns within a total process, and hide

the details of the different concerns in different containers. In CFEngine, this is a

service oriented view, in which different aspects of a problem are

separated and turned into generic components that offer a service. We

often talk about black boxes, grey boxes or white boxes depending on

the extent to which the user of a service can see the details within

the containers.

What is orchestration?

Orchestration is the ability to coordinate many different processes in

time and space, around a system, so that the sum of those processes

yields a harmonious result through cooperation.

Orchestration is not about centralized control, though this is common

misperception. An orchestra does not manage to play a symphony

because the conductor pulls every player's strings or blows every

trumpet in person, but rather because each autonomous player has a

copy of the script, knows what to do, and can use just the little

additional information from the conductor to access a viewpoint that

is not available to an individual. An orchestra is a weakly coupled

expert system in which the management (conductor) provides a service

to the players.

CFEngine works like an orchestra – this is why is scales so well.

Each computer is an autonomous entity, getting its script and a few

occasional pieces of information from the policy server (conductor).

The coupling between the agents is weak – there is slack that makes

the behaviour robust to minor errors in communication or timing.

How does CFEngine deal with modularity and orchestration?

Promise Theory provides simple principles for hiding details: agents are

considered to reveal a kind of service interface to peers, that is

advertised by making a promise to someone. We assume an agent exerts

best effort in keeping its promises. Orchestration requires a promise

to coordinate and the promise to use that coordination service.

These basic ideas are built into CFEngine.

CFEngine provides containers called bundles for creating modular

parts. Bundles can be independent (and therefore parallelizable)

or they can be dependent (in which case the sequence in which they

verify their promises matters).

In a computer centre with many different machines, there is an

additional dimension to orchestration – multiple orchestras. Each

machine has a number of resources that need to be orchestrated, and

the different machines themselves might also need to cooperate because

they provide services to one another. The principles are the same in

both cases, but the confusion between them is typically the reason why

large systems do not scale well.

Levels of policy abstraction

CFEngine offers a number of layers of abstraction. The most fundamental atom

in CFEngine is the promise. Promises can be made about many system issues,

and you described in what context promises are to be kept.

- Menu level

- At this high level, a user `selects' from a set of pre-defined `services' (or bundles in CFEngine parlance).

In commercial editions, users may view the set of services as a Service Catalogue, from which each

host selects its roles. The selection is not made by every host, rather one places hosts into roles that

will keep certain promises, just as different voices in an orchestra are assigned certain parts to play.

bundle agent service_catalogue # menu

{

methods:

any:: # selected by everyone

"everyone" usebundle => time_management,

comment => "Ensure clocks are synchronized";

"everyone" usebundle => garbage_collection,

comment => "Clear junk and rotate logs";

mailservers:: # selected by hosts in class

"mail server" -> { "goal_3", "goal_1", "goal_2" }

usebundle => app_mail_postfix,

comment => "The mail delivery agent";

"mail server" -> goal_3,

usebundle => app_mail_imap,

comment => "The mail reading service";

"mail server" -> goal_3,

usebundle => app_mail_mailman,

comment => "The mailing list handler";

}

|

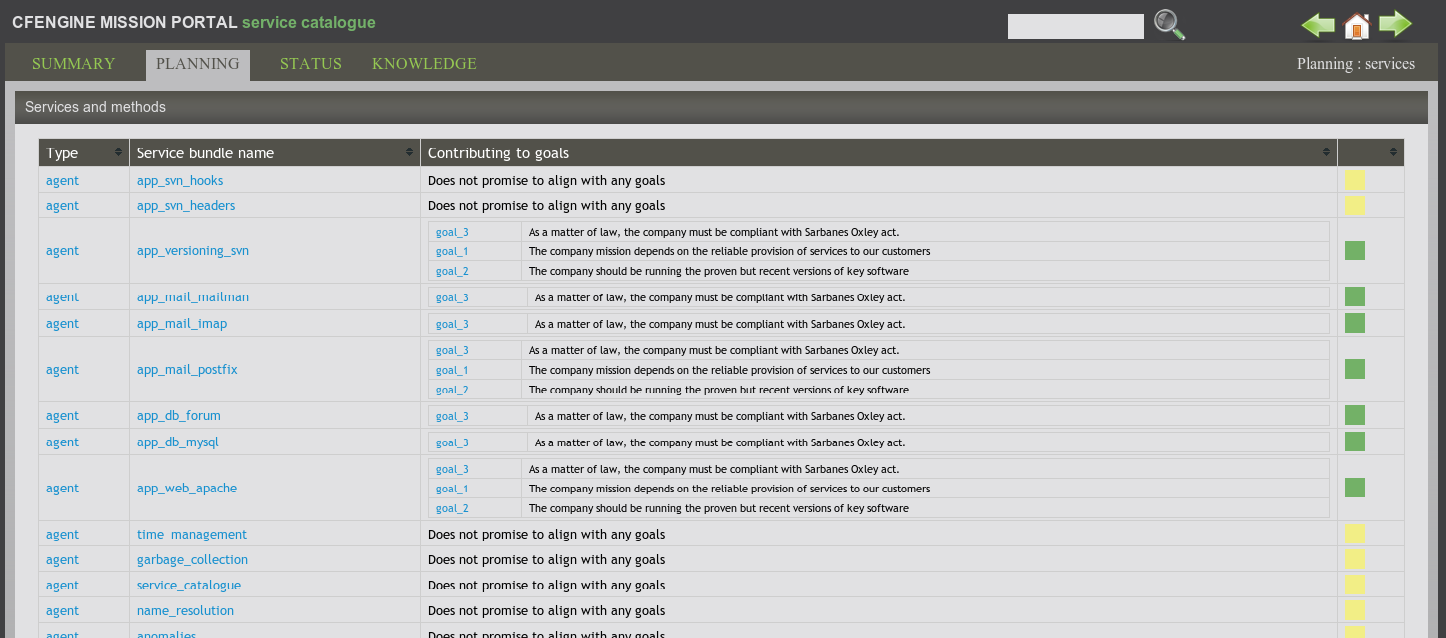

The resulting menu of services can be browsed in the Mission Portal interface.

A human-readable Service Catalogue generated from technical specifications

shows what goals are being attended to automatically

- Bundle level

- At this level, users can switch on and off predefined features, or re-use

standard methods, e.g. for editing files:

body common control

{

bundlesequence => {

webserver("on"),

dns("on"),

security_set("on"),

ftp("off")

};

}

|

The set of bundles that can be selected from is extensible by the user.

- Promise level

- This is the most detailed level of configuration, and gives full

convergent promise behaviour to the user. At this promise level,

you can specificy every detail of promise-keeping behaviour, and

combine promises together, reusing bundles and methods from standard

libraries, or creating your own.

bundle agent addpasswd

{

vars:

# want to set these values by the names of their array keys

"pwd[mark]" string => "mark:x:1000:100:Mark B:/home/mark:/bin/bash";

"pwd[fred]" string => "fred:x:1001:100:Right Said:/home/fred:/bin/bash";

"pwd[jane]" string => "jane:x:1002:100:Jane Doe:/home/jane:/bin/bash";

files:

"/etc/passwd" # Use standard library functions

create => "true",

comment => "Ensure listed users are present",

perms => mog("644","root","root"),

edit_line => append_users_starting("addpasswd.pwd");

}

|

- Spread-sheet level (data-driven)

-

CFEngine commercial editions support a kind of spreadsheet. In a spreadsheet

approach, you create only the data to be inserted into predefined

promises. The data are entered in tabular form, and may be browsed in

the web interface. This form of entry is preferred in some

environments, especially on the Windows platform.

Is CFEngine patch-oriented or package-oriented?

Some system management products are patching systems. They package lumps

of software and configuration along with scripts. If something goes wrong

they simply update or replace the package with a new one. This is a patching

model of system installation, but it is not a good model for repair as it nearly

always leads to interruption of service or even requires a reboot.

Installation of packages overwrites too much data in one go to be an effective model

of simple repair1. It can be both ineffecient and destructive. CFEngine manages addressable

entities at the lowest possible level so that ultra-fine-grained repair can be

performed with no interruption of service, e.g. altering a field within a line in a file,

or restarting one process, or altering one bit of a flag in each file in a set of directories.

The power to express sophisticated patterns is what makes CFEngine's approach both

non-intrusive and robust.

High level services in CFEngine

CFEngine is designed to handle high level simplicity (without

sacrificing low level capability) by working with configuration

patterns, after all configuration is all about promising

consistent patterns of system state in the resources of the

system. Lists, for instance, are a particularly common kind of

pattern: for each of the following... make a similar promise.

There are several ways to organize patterns, using containers, lists

and associative arrays. Let's look at how to configure a number of

application services.

At the simplest or highest level, we can turn services into "genes"

to switch on and off on your basic "stem cell" machines.

body agent control

{

bundlesequence => {

webserver("on"),

dns("on"),

security_set("on"),

ftp("off")

};

}

This obviously looks simple, but this kind of simplicity is cheating

as we are hiding all the details of what is going to happen – we

don't know if they are hard-coded, or whether we can decide

ourselves. Anyone can play that game! The true test is whether we can

retain the power to decide the low-level details without having to

program in a low level language like Ruby, Python or Perl. Let's peel

back some of the layers, knowing that we can hide as many of the

details as we like.

A simple, but low level approach to deploying a service, that veteran

users will recognize, is the following. This is a simple example of

orchestration between a promise to raise a signal about a missing process and

another promise to restart said process once its absence has been

discovered and signalled.

bundle agent application_services

{

processes:

"sshd" restart_class => "start_ssh";

"httpd" restart_class => "start_spache";

commands:

start_ssh::

"/etc/init.d/sshd restart";

start_apache::

"/etc/init.d/apache restart";

}

But the first thing we see is that there is a repeated pattern, so we could

rewrite this as a single promise for a list of services, at the cost of a loss

of transparency. However, this is the power of abstraction.

bundle agent application_services

{

vars:

"service" slist => { "ssh", "apache", "mysql" };

#

# Apply the following promises to this list...

#

services:

"$(service)";

}

Hiding details

Resource abstraction, or hiding system specific details inside a kind of

grey-box, is just another service as far as CFEngine is concerned – and we

generally map services to bundles.

Many system variables are discovered automatically by CFEngine and provided

"out of the box", e.g. the location of the filesystem table might be /etc/fstab,

or /etc/vfstab or even /etc/filesystems, but CFEngine allows you to

refer simply to <b>$(sys.fstab)</b>. Soft-coded abstraction needs cannot

be discovered by the system however.

So how do we create this mythical resource abstraction layer? It is

simple. Elsewhere we have defined basic settings.

bundle common res # abstraction layer

{

vars:

solaris::

"cfg_file[ssh]" string => "/etc/sshd_config";

"daemon[ssh] " string => "sshd";

"start[ssh] " string => "/etc/init.d/sshd restart";

linux.SuSE::

"cfg_file[ssh]" string => "/etc/ssh/sshd_config";

"daemon[ssh] " string => "sshd";

"start[ssh] " string => "/etc/init.d/sshd restart";

default::

"cfg_file[ssh]" string => "/etc/sshd_config";

"daemon[ssh] " string => "sshd";

"start[ssh] " string => "/etc/init.d/sshd restart";

classes:

"default" and => { "!SuSE", "solaris" };

}

Some of the attempts to recreate a CFEngine-like tool try to hard code

many decisions, meaning that minor changes in operating system versions

require basic recoding of the software. CFEngine does not make decisions

for you without your permission.

Black, grey and white box encapsulation in CFEngine

CFEngine's ability to abstract system decisions as promises also

applies to bundles of promises. After all, we can package promises

as bumper compendia for grouping together related matters in

a single package. Naturally, CFEngine never abandons its insistence

on <b>convergence</b>, merely for the sake of making things look

simple. Using CFEngine, you can create convergent orchestration.

bundle agent services

{

vars:

"service" slist => { "dhcp", "ntp", "sshd" };

methods:

"any" usebundle => fix_service("$(service)"),

comment => "Make sure the basic application services are running";

}

The code above is all you really want to see. The rest can be hidden in libraries that

you rarely look at. In CFEngine, we want the intentions to shine forth and the

low level details to be clear on inspection, but hidden from view.

We can naturally modularize the packaged bundle of fully convergent

promises and keep it as library code for reuse. Notice that

CFEngine adds comments in the code that follow processes through

execution, allowing you to see the full intentions behind the

promises in logs and error messages. In commercial versions, you can

trace these comments to see your process details.

bundle agent fix_service(service)

{

files:

"$(res.cfg_file[$(service)])"

#

# reserved_word => use std templates, e.g. cp(), p(), or roll your own

#

copy_from => cp("$(g.masterfiles)/$(service)","policy_host.mydomain"),

perms => p("0600","root","root"),

classes => define("$(service)_restart", "failed"),

comment => "Copy a stock configuration file template from repository";

processes:

"$(res.daemon[$(service)])"

restart_class => canonify("$(service)_restart"),

comment => "Check that the server process is running...";

commands:

"$(res.start[$(service)])"

comment => "Method for starting this service",

ifvarclass => canonify("$(service)_restart");

}

Bulk operations are handled by repeating patterns over lists

The power of CFEngine is to be able to handle lists of similar

patterns in a powerful way. You can also wrap the whole experience in

a method-bundle, and we can extend this kind of pattern to

implement other interfaces, all without low level programming.

#

# Remove certain services from xinetd - for system hardening

#

bundle agent linux_harden_methods

{

vars:

"services" slist => {

"chargen",

"chargen-udp",

"cups-lpd",

"finger",

"rlogin",

"rsh",

"talk",

"telnet",

"tftp"

};

methods:

#

# for each $(services) in @(services) do disable_xinetd($(services))

#

"any" usebundle => disable_xinetd("$(services)");

}

In the library of generic templates, we may keep one or more methods for implementing

service disablement. For example, this simple interface to Linux's chkconfig

is one approach, which need not be hard-coded in Ruby using Cfeninge.

#

# For the standard library

#

bundle agent disable_xinetd(name)

{

vars:

"status"

string => execresult("/sbin/chkconfig --list $(name)", "useshell");

classes:

"on" expression => regcmp(".*on","$(status)");

"off" expression => regcmp(".*off","$(status)");

commands:

on::

"/sbin/chkconfig $(name) off",

comment => "disable $(name) service";

reports:

on::

"disable $(name) service.";

off::

"$(name) has been already disabled. Don't need to perform the action.";

}

Ordering operations in CFEngine

Ordering of operations is less important than you probably

think. We are taught to think of computing as an linear sequence of

steps, but this ignores a crucial fact about distributed systems: that

many parts are independent of each other and exist in parallel.

Nevertheless there are sometimes cases of strong inter-dependency

(that we strive to avoid, as they lead to most of the difficulties of

system management) where order is important. In re-designing

CFEngine, we have taken a pragmatic approach to ordering. Essentially,

CFEngine takes care of ordering for you for most cases – and you can

override the order in three ways:

- CFEngine checks promises of the same type in the order in which they are defined, unless overridden

- Bulk ordering of composite promises (called bundles) is handled using an overall list using the bundlesequence (replaces the actionsequence in previous CFEngines)

- Dependency coupling through dynamic classes, may be used to guarantee ordering in the few cases

where this is required, as in the example below:

Bundle ordering

There are two methods, working at different levels.

At the top-most level there is the master bundlesequence

body common control

{

bundlesequence => { "bundle_one", "bundle_two", "bundle_three" };

}

For simple cases this is good enough, but the main

purpose of the bundlesequence is to easily be able to switch on

or off bundles by commenting them out.

A more flexible way of ordering bundles is to wrap the ordered process

in a master-bundle. Then you can create new sequences of bundles

(parameterized in more sophisticated ways) using methods

promises. Methods promises are simply promises to re-use bundles,

possibly with different parameters.

The default behaviour is to retain the order of these promises; the effect

is to `execute' these bundles in the assumed order:

bundle agent a_bundle_subsequence

{

methods:

classes::

"any" usebundle => bundle_one("something");

"any" usebundle => bundle_two("something");

"any" usebundle => bundle_three("something");

}

Alternatively, the same effect can be achieved as follows.

bundle agent a_bundle_subsequence

{

methods:

classes::

"any" usebundle => generic_bundle("something","one");

"any" usebundle => generic_bundle("something","two");

"any" usebundle => generic_bundle("something","three");

}

Or ultimately:

bundle agent a_bundle_subsequence

{

vars:

"list" slist => { "one", "two", "three"};

methods:

classes::

"any" usebundle => generic_bundle("something","$(list)");

}

Overriding order

CFEngine is designed to handle non-deterministic events, such as

anomalies and unexpected changes to system state, so it needs to

adapt. For this, there is no deterministic solution and approximate

methods are required. Nevertheless, it is possible to make CFEngine

sort out dependent orderings, even when confounded by humans, as in

this example:

bundle agent order

{

vars:

"list" slist => { "three", "four" };

commands:

ok_later::

"/bin/echo five";

any::

"/bin/echo one" classes => define("ok_later");

"/bin/echo two";

"/bin/echo $(list)";

}

The output of which becomes:

Q: ".../bin/echo one": one

Q: ".../bin/echo two": two

Q: ".../bin/echo three": three

Q: ".../bin/echo four": four

Q: ".../bin/echo five": five

Distributed Orchestration between hosts with CFEngine Enterprise

CFEngine Enterprise edition adds many powerful features to CFEngine, including

a decentralized approach to coordinating activities across multiple

hosts. Some tools try to approach this by centralizing data from the

network in a single location, but this has two problems:

- It leads to a bottleneck by design that throttles performance seriously.

- It relies on the network being available.

With CFEngine Nova there are are both decentralized network approaches

to this problem, and probabilistic methods that do not require the network

at all.

Basic communication methods for orchestration

The two examples below illustrate the basic syntax constructions for

communication using systems. We can pass class data and variable data between

systems in a peer to peer fashion, or through an Enterprise hub. You can

run these with a server and an agent just on localhost to illustrate the

principles.

In this first example, three persistent classes, with names following

a known pattern are defined on a remote system (by the agent). The

server bundle then grants access to these using an access

promise. Finally, a function call to remoteclassesmatching

imports the classes, with a prefix to the local system.

body common control

{

bundlesequence => { "overture" };

inputs => { "cfengine_stdlib.cf" };

}

body server control

{

allowconnects => { "127.0.0.1" , "::1",};

allowallconnects => { "127.0.0.1" , "::1", };

trustkeysfrom => { "127.0.0.1" , "::1",};

}

#######################################################

bundle agent overture

{

classes:

"extended_context"

expression => remoteclassesmatching(".*did.*","127.0.0.1","yes","got");

files:

"/etc/passwd"

create => "true",

classes => set_outcome_classes;

reports:

got_did_task_one::

"task 1 complete";

extended_context.got_did_task_two::

"task 2 complete";

extended_context.got_did_task_three::

"task 3 complete";

}

body classes set_outcome_classes

{

promise_kept => { "did_task_one","did_task_two", "did_task_three" };

promise_repaired => { "did_task_one","did_task_two", "did_task_three" };

#cancel_kept => { "did_task_one" };

persist_time => "10";

}

bundle server access_rules()

{

access:

"did.*"

resource_type => "context",

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

}

The output of this, on success is simply:

R: task 1 complete

R: task 2 complete

R: task 3 complete

In this second example, we pass actual variable data between hosts.

The generic peer function remotescalar can address any other host

running cf-serverd. The abbreviated interface hubknowledge

assumes that it should get data from a hub.

Both these functions ask for an identifier; it is up to the server to interpret

what this means and to return a value of its choosing. If the identifier matches

a persistent scalar variable (such as is used to count distributed processes in CFEngine

Enterprise) then this will be returned preferentially. If no such variable is found,

then the server will look for a literal string in a server bundle with a handle that

matches the requested object.

body common control

{

bundlesequence => { "overture" };

inputs => { "cfengine_stdlib.cf" };

}

body server control

{

allowconnects => { "127.0.0.1" , "::1",};

allowallconnects => { "127.0.0.1" , "::1", };

trustkeysfrom => { "127.0.0.1" , "::1",};

}

#######################################################

bundle agent overture

{

vars:

"remote" string => remotescalar("test_scalar","127.0.0.1","yes");

"know" string => hubknowledge("test_scalar");

"count_getty" string => hubknowledge("count_getty");

processes:

# Use the enumerated library body to count hosts running getty

"getty"

comment => "Count this host if a job is matched",

classes => enumerate("count_getty");

reports:

!elsewhere::

"GOT remote scalar $(remote)";

"GOT knowedge scalar $(know)";

"GOT persistent scalar $(xyz)";

}

#######################################################

bundle server access_rules()

{

access:

"value of my test_scalar, can expand variables here - $(sys.host)"

handle => "test_scalar",

comment => "Grant access to contents of test_scalar VAR",

resource_type => "literal",

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

"XYZ"

resource_type => "variable",

handle => "XYZ",

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

}

You can run this example on a single host, running the server, the agent and the hub (if you have Enterprise CFEngine).

The output will be something like this:

host$ ./cf-agent -f ~/test.cf -K

R: GOT remote scalar value of my test_scalar, can expand variables here - cflu-10004

R: GOT knowedge scalar value of my test_scalar, can expand variables here - cflu-10004

R: GOT persistent scalar 1

Run job or reboot only if n out m systems are running

The ability to base local promises on global knowledge seems

superficially attractive in some cases. As a strategy this way of

thinking requires a lot of caution. We have to assume that all

knowledge gathered about an environment is subject to errors,

latencies and a dozen other uncertainties that make any snapshot of

remotely assessed current state subject to considerable healthy

suspicion. This is not a weakness of CFEngine – in fact CFEngine has

mechanisms that make it as reliable as you are likely to find in any

technology – rather it is a fundamental limitation of distributed

systems, and it is strongly dependent on the architectures you build.

In the following example, we show how you can make certain decisions

based on global, uncertain knowledge, allowing for the fact that the

information is uncertain. In other words, we aim to err on the safe

side. In this case we ask how could we reboot systems after an upgrade

only if doing so would not jeopardize a Service Level Agreement to have

at least 20 machines running at all times. Since the globally

counted instances of a running process cannot be greater than the actual

number, this particular problem satisfies the constraint of erring

on the side of caution.

############################################################

#

# Keep a special promise only if at least n or m hosts

# keep a specific promise

#

# This method works with Enterprise CFEngine

#

# If you want to test this on localhost, just edit /etc/hosts

# to add host1 host2 host3 host4 as aliases to localhost

#

############################################################

body common control

{

bundlesequence => { "n_of_m_symphony" };

inputs => { "cfengine_stdlib.cf" };

}

############################################################

bundle agent n_of_m_symphony

{

vars:

"count_compliant_hosts" string => hubknowledge("running_myprocess");

classes:

"reboot" expression => isgreaterthan("$(count_compliant_hosts)","20");

processes:

"myprocess"

comment => "Count this host if a job is matched",

classes => enumerate("running_myprocess");

commands:

reboot::

"/bin/shutdown now";

}

#######################################################

bundle server access_rules()

{

access:

"value of my test_scalar, can expand variables here - $(sys.host)"

handle => "test_scalar",

comment => "Grant access to contents of test_scalar VAR",

resource_type => "literal",

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

"running_myprocess"

resource_type => "variable",

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

}

The self-healing chain - inverse Dominoes

A self-healing chain is the opposite of a dominoe event. If a part of

the chain is `down', it will be revived. If these events depend on one

another, then the resuscitation of this part which cause all of the

subsequent parts to be repaired too.

Let's start with the more common case of the independently repairable

services, such as one might find in a multi-tier architecture:

database, web-servers, applications etc.

The following example can be run on a multiple hosts or on a single

host, using the aliases described in the example. It illustrates

coordination through the use of CFEngine's remoteclasses

function in the Enterprise edition to get confirmation of the

self-healing structure. In fact, the verification of the self-healing

is optional if one trusts the underlying system.

############################################################

#

# The self-healing tower: Anti-Dominoes

#

# This method works with CFEngine Enterprise

#

# If you want to test this on localhost, just edit /etc/hosts

# to add host1 host2 host3 host4 as aliases to localhost

#

############################################################

body common control

{

bundlesequence => { "weak_dependency_symphony" };

inputs => { "cfengine_stdlib.cf" };

}

body server control

{

allowconnects => { "127.0.0.1" , "::1", @(def.acl) };

allowallconnects => { "127.0.0.1" , "::1", @(def.acl) };

}

############################################################

bundle agent weak_dependency_symphony

{

methods:

# We have to seed the beginning by creating the tower

# /tmp/tower_localhost

host1::

"tower" usebundle => tier1,

classes => publish_ok("ok_O");

host2::

"tower" usebundle => tier2,

classes => publish_ok("ok_1");

host3::

"tower" usebundle => tier3,

classes => publish_ok("ok_2");

host4::

"tower" usebundle => tier4,

classes => publish_ok("ok_f");

classes:

ok_O:: # Wait for the methods, report on host1 only

"check1" expression => remoteclassesmatching("ok.*","host2","yes","a");

"check2" expression => remoteclassesmatching("ok.*","host3","yes","a");

"check3" expression => remoteclassesmatching("ok.*","host4","yes","a");

reports:

ok_O::

"tier 1 is ok";

a_ok_1::

"tier 2 is ok";

a_ok_2::

"tier 3 is ok";

a_ok_f::

"tier 4 is ok";

ok_O&a_ok_1&a_ok_2&a_ok_f::

"The Tower is standing";

!(ok_O&a_ok_1&a_ok_2&a_ok_f)::

"The Tower is down";

}

############################################################

bundle agent tier1

{

files:

"/tmp/something_to_do_1"

create => "true";

}

bundle agent tier2

{

files:

"/tmp/something_to_do_2"

create => "true";

}

bundle agent tier3

{

files:

"/tmp/something_to_do_3"

create => "true";

}

bundle agent tier4

{

files:

"/tmp/something_to_do_4"

create => "true";

}

############################################################

bundle server access_rules()

{

access:

"ok.*"

resource_type => "context",

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

}

############################################################

body classes publish_ok(x)

{

promise_repaired => { "$(x)" };

promise_kept => { "$(x)" };

cancel_notkept => { "$(x)" };

persist_time => "2";

}

If we execute this simple test on a single host, or allow it to be executed on distributed

hosts, the chain forms and quickly stands up the system into a tower of dependencies.

host$ ~/LapTop/cfengine/core/src/cf-agent -f ~/orchestrate/self-healing-chain.cf -K

R: tier 1 is ok

R: tier 2 is ok

R: tier 3 is ok

R: tier 4 is ok

R: The Tower is standing

If we break the tower, by giving it an impossible promise to keep, e.g. changing the name

of the directory in tier 3 to something that cannot be created2,

then tier 3 will fail and the output looks like this:

host$ ~/LapTop/cfengine/core/src/cf-agent -f ~/orchestrate/self-healing-chain.cf -K

Unable to make directories to /xtmp/something_to_do_3

!!! System reports error for cf_mkdir: "Permission denied"

R: tier 1 is ok

R: tier 2 is ok

R: tier 4 is ok

R: The Tower is down

Clearly, whatever tier 3 is really supposed to do, any promise failure

would result in the same behaviour. If we then correct the policy to make it repairable, the output

heals quickly:

host$ ~/LapTop/cfengine/core/src/cf-agent -f ~/orchestrate/self-healing-chain.cf -K

R: tier 1 is ok

R: tier 2 is ok

R: tier 4 is ok

R: The Tower is down

R: tier 3 is ok

R: The Tower is standing

A Domino sequence

A different kind of orchestration is a domino cascade, that starts

from some initial trigger, and causes a change in one host that causes

a change in the next, etc. These examples show how this can easily be

carried out by CFEngine. Dominio cascades can be done with Community

or Enterprise editions, but are limited to single machines in each

step.

The basic principle is shown below3.

Note: to simulate this on a single host, start the server and agent

with this same file as input, and make aliases to localhost in /etc/hosts

as described in the example.

############################################################

#

# Dominoes

#

# This method works with either Community of Enterprise

#

# If you want to test this on localhost, just edit /etc/hosts

# to add host1 host2 host3 host4 as aliases to localhost

#

############################################################

body common control

{

bundlesequence => { "dominoes_symphony" };

inputs => { "cfengine_stdlib.cf" };

}

############################################################

bundle agent dominoes_symphony

{

methods:

# We have to seed the beginning by creating the dominoes

# /tmp/dominoes_localhost

host1::

"dominoes" usebundle => hand_over("localhost","host1","overture");

host2::

"dominoes" usebundle => hand_over("host1","host2","first_movement");

host3::

"dominoes" usebundle => hand_over("host2","host3","second_movement");

host4::

"dominoes" usebundle => hand_over("host3","host4","final_movement"),

classes => if_ok("finale");

reports:

finale::

"The visitors book of the Dominoes method"

printfile => visitors_book("/tmp/dominoes_host4");

}

############################################################

bundle agent hand_over(predecessor,myalias,method)

{

# This is a wrapper for the orchestration

files:

"/tmp/tip_the_dominoes"

comment => "Wait for our cue or relay/conductor baton",

copy_from => secure_cp("/tmp/dominoes_$(predecessor)","$(predecessor)"),

classes => if_repaired("cue_action");

methods:

cue_action::

"the music happens"

comment => "One off activity",

usebundle => $(method),

classes => if_ok("pass_the_stick");

files:

pass_the_stick::

"/tmp/tip_the_dominoes"

comment => "Add our signature to the dominoes's tail",

edit_line => append_if_no_line("Knocked over $(myalias) and did: $(method)");

"/tmp/dominoes_$(myalias)"

comment => "Dominoes in position to be beamed up by next agent",

copy_from => local_cp("/tmp/tip_the_dominoes");

}

############################################################

bundle agent overture

{

reports:

!xyz::

"Singing the overture...";

}

bundle agent first_movement

{

reports:

!xyz::

"Singing the first adagio...";

}

bundle agent second_movement

{

reports:

!xyz::

"Singing second allegro...";

}

bundle agent final_movement

{

reports:

!xyz::

"Trumpets for the finale";

}

############################################################

bundle server access_rules()

{

access:

"/tmp"

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

"did.*"

resource_type => "context",

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

}

body printfile visitors_book(file)

{

file_to_print => "$(file)";

number_of_lines => "10";

}

When executed, this produces output only on the final host

in the chain, showing the correct ordering out operations. The

sequence also passes a file from host to host as a coordination

token, like a baton in a relay race, and each host signs this

so that the final host has a log of eery host involved in the

cascade.

R: Singing the overture...

R: Singing the first adagio...

R: Singing second allegro...

R: Trumpets for the finale

R: The visitors book of the Dominoes method

R: Knocked over host1 and did: overture

R: Knocked over host2 and did: first_movement

R: Knocked over host3 and did: second_movement

R: Knocked over host4 and did: final_movement

The average time for such a cascade to complete will be half the

length of the chain multiplied by the run-interval, if normal cf-execd

splaytime is used. Without any splaying, the average time will be the

run interval multiplied by the chain length. The completion time

could be increased by using cf-runagent.

A Chinese Dragon star pattern

The Chinese dragon darts back and forth between different hosts,

forming a chain of events, and leaving a trail behind it. This pattern

is much like the Domino pattern, except that it follows a star. The

orchestrated sequence of events follows the dragon from its lair to

the first satellite host, then back to its lair to record the journey,

then out to the next satellite, then back to its lair, etc.

A prototypical application for this kind of pattern is taking servers, one by one,

off a load balancer (in the dragon's lair) and then upgrading them, before

reinstating them and moving on to the next host.

############################################################

#

# Chinese Dragon Dancing on a Star

#

# This method works with either Community or Enterprise.

# and uses named signals

#

# If you want to test this on localhost, just edit /etc/hosts

# to add host1 host2 host3 host4 as aliases to localhost

#

############################################################

body common control

{

bundlesequence => { "dragon_symphony" };

inputs => { "cfengine_stdlib.cf" };

}

############################################################

bundle agent dragon_symphony

{

methods:

# We have to seed the beginning by creating the dragon

# /tmp/dragon_localhost

"dragon" usebundle => visit("localhost","host1","chapter1");

"dragon" usebundle => visit("host1","host2","chapter2");

"dragon" usebundle => visit("host2","host3","chapter3");

"dragon" usebundle => visit("host3","host4","chapter4"),

classes => if_ok("finale");

reports:

finale::

"The dragon is slain:"

printfile => visitors_book("/tmp/shoo_dragon_host4");

}

############################################################

# Define the

############################################################

bundle agent chapter1(x)

{

# Do something significant here

reports:

host1::

" ----> Breathing fire on $(x)";

}

################################

bundle agent chapter2(x)

{

# Do something significant here

reports:

host2::

" ----> Breathing fire on $(x)";

}

################################

bundle agent chapter3(x)

{

# Do something significant here

reports:

host3::

" ----> Breathing fire on $(x)";

}

################################

bundle agent chapter4(x)

{

# Do something significant here

reports:

host4::

" ----> Breathing fire on $(x)";

}

############################################################

# Orchestration wrappers

############################################################

bundle agent visit(predecessor,satellite,method)

{

# This is a wrapper for the orchestration will be acted on

# first by the dragon's lair and then by the satellite

vars:

"dragons_lair" string => "host0";

files:

# We start in the dragon's lair ..

"/tmp/unleash_dragon"

comment => "Unleash the dragon",

rename => to("/tmp/enter_the_dragon"),

classes => if_repaired("dispatch_dragon_$(satellite)"),

ifvarclass => "$(dragons_lair)";

# if we are the dragon's lair, welcome the dragon back, shooed from the satellite

"/tmp/enter_the_dragon"

comment => "Returning from a visit to a satellite",

copy_from => secure_cp("/tmp/shoo_dragon_$(predecessor)","$(predecessor)"),

classes => if_repaired("dispatch_dragon_$(satellite)"),

ifvarclass => "$(dragons_lair)";

# If we are a satellite, receive the dragon from its lair

"/tmp/enter_the_dragon"

comment => "Wait for our cue or relay/conductor baton",

copy_from => secure_cp("/tmp/dragon_$(satellite)","$(dragons_lair)"),

classes => if_repaired("cue_action_on_$(satellite)"),

ifvarclass => "$(satellite)";

methods:

"check in at home"

comment => "Edit the load balancer?",

usebundle => switch_satellite(" -> Send dragon to $(satellite)"),

classes => if_repaired("send_the_dragon_to_$(satellite)"),

ifvarclass => "dispatch_dragon_$(satellite)";

"dragon visits"

comment => "One off activity that the nodes carry out while the dragon visits",

usebundle => $(method)("$(satellite)"),

classes => if_repaired("send_the_dragon_back_from_$(satellite)"),

ifvarclass => "cue_action_on_$(satellite)";

files:

# hub/lair hub signs the book too and schedules the dragon for next satellite

"/tmp/dragon_$(satellite)"

create => "true",

comment => "Add our signature to the dragon's tail",

edit_line => sign_visitor_book("Dragon returned from $(predecessor)"),

ifvarclass => "send_the_dragon_to_$(satellite)";

# Satellite signs the book and shoos dragon for hub to collect

"/tmp/shoo_dragon_$(satellite)"

create => "true",

comment => "Add our signature to the dragon's tail",

edit_line => sign_visitor_book("Dragon visited $(satellite) and did: $(method)"),

ifvarclass => "send_the_dragon_back_from_$(satellite)";

reports:

!xyz::

"Done $(satellite)";

}

############################################################

bundle agent switch_satellite(name)

{

files:

"/tmp/enter_the_dragon"

comment => "Add our signature to the dragon's tail",

edit_line => append_if_no_line("Switch new dragon's target $(name)");

reports:

!xyz::

" X Switching new dragon's target $(name)";

}

############################################################

bundle edit_line sign_visitor_book(s)

{

insert_lines:

"/tmp/enter_the_dragon"

comment => "Import the current visitor's book",

insert_type => "file";

"$(s)" comment => "Append this string to the visitor's book";

}

############################################################

bundle server access_rules()

{

access:

"/tmp"

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

"did.*"

resource_type => "context",

admit => { "127.0.0.1" };

}

############################################################

body printfile visitors_book(file)

{

file_to_print => "$(file)";

number_of_lines => "100";

}

Let's test it on a single host, equipped with aliases to the see entire flow.

Without the trigger, this simply yields

R: Done host1

R: Done host2

R: Done host3

R: Done host4

host$ touch /tmp/unleash_dragon

host$ ~/LapTop/cfengine/core/src/cf-agent -f ~/orchestrate/dragon.cf -K

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host1

R: Done host1

R: Done host2

R: Done host3

R: Done host4

host$ ~/LapTop/cfengine/core/src/cf-agent -f ~/orchestrate/dragon.cf -K

R: ----> Breathing fire on host1

R: Done host1

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host2

R: Done host2

R: Done host3

R: Done host4

host$

host$ ~/LapTop/cfengine/core/src/cf-agent -f ~/orchestrate/dragon.cf -K

R: ----> Breathing fire on host1

R: Done host1

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host2

R: ----> Breathing fire on host2

R: Done host2

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host3

R: Done host3

R: Done host4

host$ ~/LapTop/cfengine/core/src/cf-agent -f ~/orchestrate/dragon.cf -K

R: ----> Breathing fire on host1

R: Done host1

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host2

R: ----> Breathing fire on host2

R: Done host2

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host3

R: ----> Breathing fire on host3

R: Done host3

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host4

R: Done host4

host$ ~/LapTop/cfengine/core/src/cf-agent -f ~/orchestrate/dragon.cf -K

R: ----> Breathing fire on host1

R: Done host1

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host2

R: ----> Breathing fire on host2

R: Done host2

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host3

R: ----> Breathing fire on host3

R: Done host3

R: X Switching new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host4

R: ----> Breathing fire on host4

R: Done host4

R: The dragon is slain:

R: Switch new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host1

R: Dragon returned from localhost

R: Dragon visited host1 and did: chapter1

R: Switch new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host2

R: Dragon returned from host1

R: Dragon visited host2 and did: chapter2

R: Switch new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host3

R: Dragon returned from host2

R: Dragon visited host3 and did: chapter3

R: Switch new dragon's target -> Send dragon to host4

R: Dragon returned from host3

R: Dragon visited host4 and did: chapter4