A menu is a list of simple choices. The purpose of a menu is to hide the detailed breakdown of how those choices are implemented. A menu item uses a single name to represent all the processes needed to bring about the result. Naming things is an important aspect of knowledge management.

Menus work well as long as the choices you are presented with are sufficient to cover your needs. If a menu is too short, it will force you to choose sub-optimally, leading to an oversimplification of your issues. This can lead to frustration and compromise.

CFEngine does not force pre-determined menus onto you, rather it allows you to make your own from building block operations. This document explains how to simplify your interface to complex configuration decisions by organizing it according to what amounts to a number of context dependent menus – i.e. menus that automatically adapt to the environments in which they are run.

| Once menus have been defined, they can be presented simply in any kind of interface, including custom graphical user interfaces. |

A menu is a list of delegated methods. To create a menu, you need to be able to name complex methods. CFEngine does this by grouping promises into bundles. You must then present these bundles in some kind of list for different machines in your environement to select from. CFEngine has two mechanisms for presenting a bundle of lists.

bundlesequence as your menu. This is the master

execution list that CFEngine uses to process work. You `choose' promise bundles there by

commenting out the ones you don't want to use:

body common control

{

bundlesequence => {

"common_stuff",

# "change_management",

# "garbage_collection",

# "harden_xinetd",

# "my_firewall",

"php_apache",

# "j_def", "jboss_account", "jboss_server",

# "ruby_on_rails",

# "tomcat_server",

# "db_mysql",

# "db_postgresql",

};

}

The advantage of the bundlesequence is that it provides a definite ordering of the bundles. In the example above, the order doesn't matter much. The disadvantage of this bundlesequence is that it is hard to adapt it to more than one environment – it is like a `set taster menu'. Every machine using this configuration will get what it's given. That is too heavy-handed for more sophisticated environments.

methods promises to embed bundles in a master-bundle,

in the manner of subroutines.

body common control

{

bundlesequence => {

"common_stuff",

"main",

};

}

bundle agent main

{

methods:

context1:: # Menu for context 1

"course2" usebundle => php_apache;

context2:: # Menu for context 2

"course2" usebundle => j_def;

"course2" usebundle => jboss_account;

"course2" usebundle => jboss_server;

any:: # Menu items for everyone

"course1" usebundle => changemanagement;

}

In this example, we've just pointed the master bundlesequence to a `main' subroutine

(like in a C program) and we list the bundles we want to combine into menus in order, in different

contexts. So in context 1, machines see a PHP menu; in context 2, they see a Java menu. Both of them

get a common `dessert' of change management.

This `method' approach makes light work of adaptation, but while the order is preserved in most cases, you cannot guarantee that CFEngine will execute the bundles in the written order, because other `transaction constraints' (including CFEngine's convergent algorithms) can interfere. In many cases ordering is less important than we have been taught to think, but if you truly need strong ordering then there are mechanisms to ensure the strict order of keeping promises.

Because CFEngine is a distributed system, every machine running CFEngine can make its own choices. You can suggest a menu for different classes of machines, that operate in different contexts.

A machine selects a menu choice by virtue of being in a context that has been defined. For instance, you might make separate menu choices based on operating system:

bundle agent main

{

methods:

ubuntu:: # Menu for context 1

"course2" usebundle => php_apache;

solaris:: # Menu for context 2

"course2" usebundle => j_def;

"course2" usebundle => jboss_account;

"course2" usebundle => jboss_server;

any:: # Menu items for everyone

"course1" usebundle => changemanagement;

}

Alternatively, you might choose based on other context information, such as the time of day, or membership in some abstract group:

bundle agent main

{

methods:

Hr16.Min45:: # Menu for context 1

"course2" usebundle => backup_system;

mygroup:: # Menu for context 2

"course2" usebundle => attach_storage_devices;

}

The expressions like ‘Hr16.Min45’ are called `class expressions' because they classify different contexts or scenarios, and CFEngine knows how to keep promises only in the correct context. This is how you select from a menu – by correctly identifying the context a system belongs to and describing the menu of promise-bundles that apply to it.

Recursion is the term used to express a hierarchy of levels of description. When a promise depends on something else, which in turn depends on a third promise being kept, we say that there is nesting or recursion.

A dependency (something we depend on to keep a promise) is often used as a strategy for hiding detail. You push details into `black boxes' on which you depend, and in doing so simpify the view for yourself. This is the menu idea once again. So when you pick a menu item in the restaurant, the kitchen breaks down your choice into a sub-menu of promises required to deliver your selection, and so on down the chain.

CFEngine allows bundles of promises to depend on other promises by

writing those promises inside the bundles. A bundle can even rely on

bundles of promises by using the methods approach

recursively. So, for example you could make a general menu choice

`setup_server', which depends on bundles `setup_general'

and `setup_solaris' and `setup_linux'.

bundle agent main

{

methods: # bulk dependency by bundle

linux::

"linux machines" usebundle => setup_linux;

solaris::

"sun machines" usebundle => setup_solaris;

any::

"all" usebundle => setup_general;

files:

# other promises

}

#

bundle agent setup_general

{

commands: # Dependenc on individual promise

Hr06::

"/usr/local/bin/do_backup"

comment => "Command dependence";

}

bundle agent setup_linux

{

packages:

ubuntu:: # Dependence on software

"apache2"

package_policy => "add",

package_method => "yum";

}

# other bundles ...

Notice how each `menu level' simplifies the appearance of the problem by hiding details in the lower levels. This is the way you make components in systems and delegate responsibility for different tasks to different bundle maintainers.

Weak dependency means that you `outsource' tasks that you will eventually make use of, i.e. you depend on the outcomes but you don't have to wait for the result. This kind of dependence brings flexibility and allows delegation.

Strong dependency means that you are completely dependent on getting the result from somewhere else before you can continue. This kind of dependence creates fragile or `brittle' systems. If part of the system breaks, then everything breaks. It leads to `single points of failure'.

We recommend avoiding strong dependency when designing systems. Whenever possible, a system should survive the temporary loss of a part, and should continue in a sensible and predictable manner.

Once you have arranged your system promises in nested bundles to handle all of the dependences, you no longer have a complete overview of the system. This is the challenge of menu hierarchies – hierarchy simplifies for individuals by offloading responsibility, but it makes it harder for anyone to get a total overview.

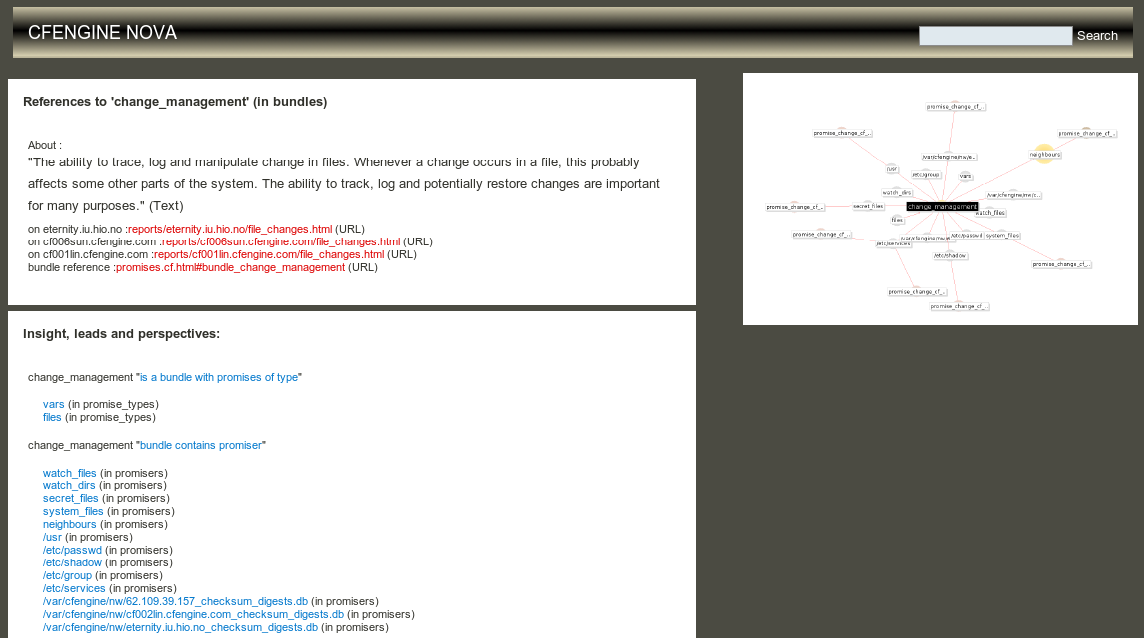

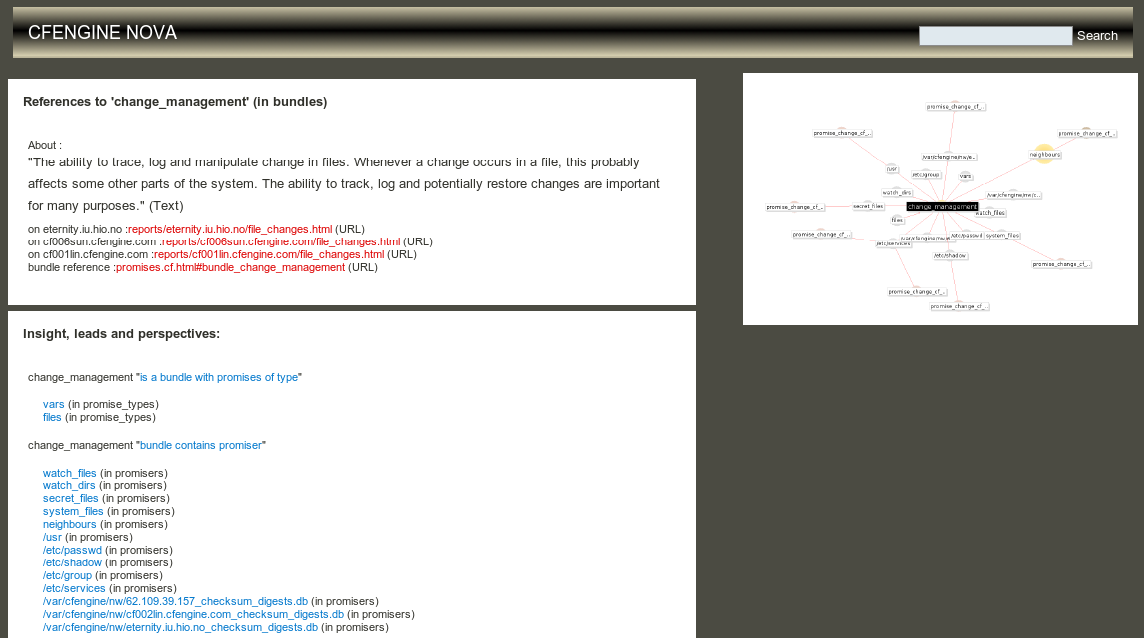

To get back to the total overview, you can use CFEngine's Knowledge Map.

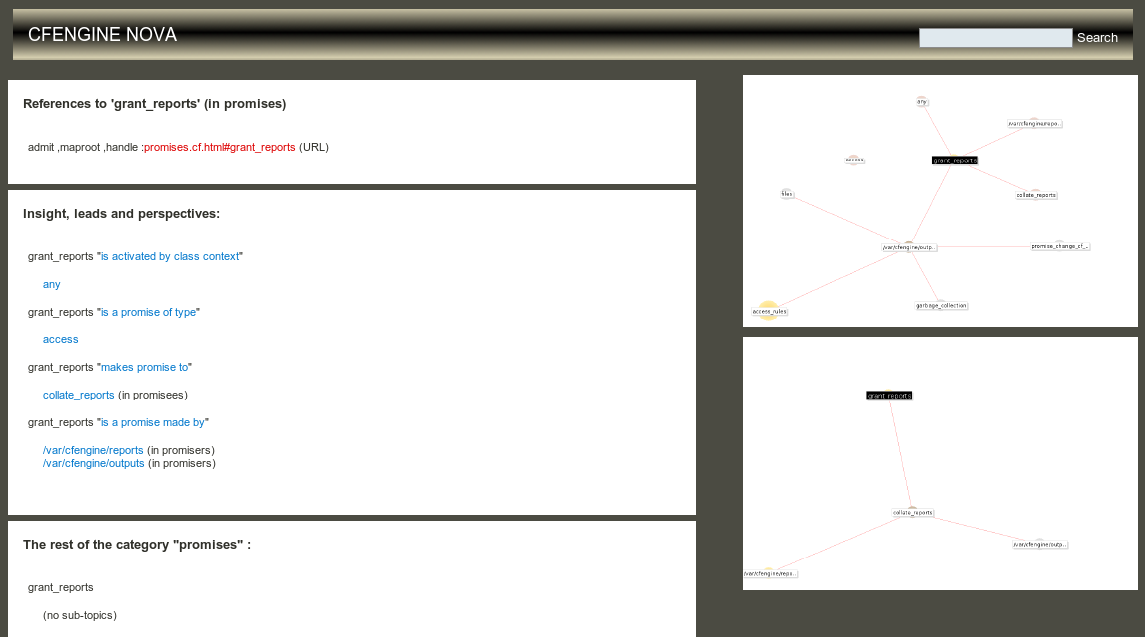

The knowledge map renders all of the relationships between promises as a lexicon and visual map. It allows you to see the total set of promises and bundles either as a generic flat network, or as a hierarchy. It also allows you to search for issues within the total network. The knowledge map puts back what the hierarchy takes away, by allowing you to construct your own view of the system.

If there are dependences they may be seen as a graphical representation of issues. The lower image in this figure shows the direct dependences of the `grant_reports' promises, i.e. all those that might be affected by a change, and all those on which this promise depends.

One reason people make lists is to be able to tick off the menu items to know when a job is complete. CFEngine allows you to measure whether all of the menu-promises have been kept, by viewing reports tied into the knowledge map.

There is one crucial difference between system configuration and menus at a restaurant though: the order of the items in the menu does not always have to be preserved, and in fact it is very inefficient to use the menu as a strictly ordered list. Computer configuration can benefit greatly from parallel execution, and CFEngine is designed to parallelize tasks for greater efficiency.

| We advise against designing systems that base their outcome on a strict ordering of promises. Although traditional programming methods teach us to think in terms of imperative ordering, you will succeed more effectively if you avoid it. |

A menu driven approach is a good way of modelling a complex environment, with delegation. It is a form of knowledge management. It allows you to view your system through a kind of compliance scorecard.

The idea of nesting layers of menus is similar to what has been advocated by Object Oriented programming languages for several years. However, OO also shows how you can go too far in creating deep and complex hierarchies that become impossible to understand. If you create too many levels, you invite inefficiency and complexity.

We recommend keeping system organization simple, and avoiding dependence whenever it does not provide a compelling and tangible benefit.