Everyone agrees that Knowledge Management is important, but few really appreciate what it means to manage knowledge, or how to begin. Ironically perhaps, even learning institutions (so-called knowledge based industries) like schools and universities often do not do a good job of this. Having a wealth of knowledge is not the same as knowing how to foster and protect it. Most organizations take their knowledge for granted.

In the worst case, poorly run organizations end up as collections of individuals, each of whom possesses knowledge and experience, but none of whom knows anything about the others' roles. This scenario presents a high risk for the continuity of the organization, since taking out even a single player could cripple a key work process.

The end result is that many organizations are caught in a poverty trap of knowledge: they spend their time reacting to emergencies cultivated by a lack of confidence and certainty, and they are too busy patching over holes that they never have time to learn enough to escape the pattern.

| The Third Wave of configuration management emphasizes the role of knowledge in coping with the diversity and adaptability that modern organizations crave. This document is a beginning towards thinking about IT management in a new way: as a knowledge resource, or a set of insight-driven intentions that are maintained by smart machinery. This vision is about rehumanizing System Administration through a proper division of labour between Man and Machine. |

Knowledge exists to reduce our uncertainty about the world. We don't generally learn in order to get smart, or to be experts; rather we learn by necessity and feel smart when there are no remaining surprises. Experts are people who can answer questions they already know the answer to; they are supposedly extra-ordinary. Innovators are people who can solve new problems – they are even rarer.

The main aim of knowledge management is not to make everyone an expert, but to improve the predictability of workflow processes so that we can respond to unpredictable changes in the environment with greater confidence, without losing the feeling of control over the situations we find ourselves in. To do that, we have to make the connections between the appropriate parts to that we can always obtain the answers.

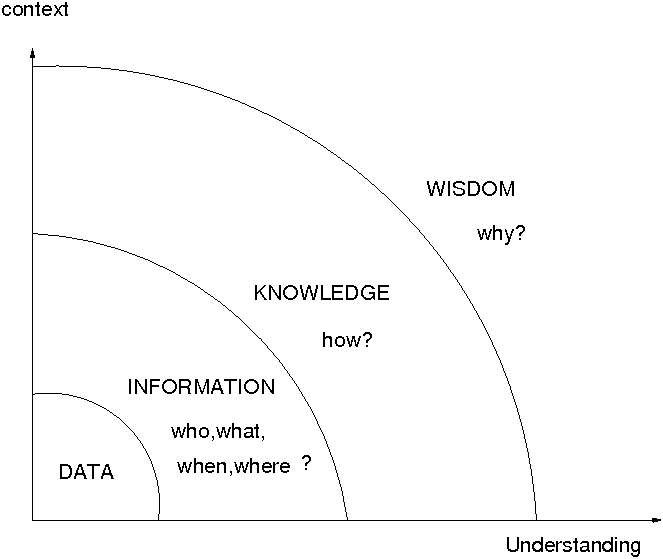

The road to maturity can be seen as stepping through one or more of the following progressions:

Each of these sequences represents an increasing level of commitment. You need to have data to interpret them as information. You need to have goals or objectives in order to realize them and see results. You need to have intentions to make promises, and so on. Ask yourself: does everyone in your team know your business goals, and how to translate their efforts into progess?

Maps guide us to where we need to get to from where we are (even when we don't fully understand where we are). A map places us in the context or a larger picture and helps us to find our way. The Knowledge map is a part of the CFEngine Mission Portal, which in turn is provided with CFEngine Enterprise Edition. Significant instrumentation of the software, user process and policy analysis are provided in these editions in order to make Knowledge mining as transparent to the user as possible.

| Our first task in Knowledge Management is to create a map of the knowledge landscape in which we work. |

CFEngine contains a tool cf-know for creating a map called a

Topic Map, that forms to basis of our approach to documentation.

Further, CFEngine Enterprise Editions, starting with Nova help fill in

the landscape of this map automatically.

To build a map, you will need data (hence the beginning of the DIKW chain). To use a map, you need an objective or an intention, hence the others.

Ask yourself: what are the places in this map, and what are the paths between them? This is a question every organization needs to ask itself.

CFEngine does a lot of work for you, but you need to do something to help yourself too. As with all information, garbage in leads to garbage out. Your organization should create documents and references to capture its internal knowledge. If you are doing this well, it should not be a major task.

Knowledge gets out of control when you don't standardize ideas, concepts and procedures. By standardizing topics and concepts, you prevent an explosion of redundancy – only then can you see the signal in the noise. Standardization minimizes the number of things you have to deal with. Be careful though, if you go too far, standardization can become a straightjacket, preventing you from clear and free expression. Too much standardization and you will be stuck in a rut.

| Dedicate yourself to a culture of simplicity, but not of over-simplification (which often backfires). Always work to avoid special cases and exceptions, unless they can be rigorously justified. |

This is a question of economics: is it worth the cost of maintaining a special case? CFEngine's is designed to make it a lot easier and cheaper to manage exceptions, so you needn't worry too much. Just don't go mad.

Simplification is the hardest thing you will ever do. Anyone can make something more complicated, but it takes real work to simplify something1. Einstein's famous quote captures this: You should always make everything as simple as possible, but no simpler.

CFEngine's exploration of knowledge management is still in its infancy – we are learning constantly about how to use state of the art technologies and techniques. This is still very much an experimental area that we continue to improve upon.

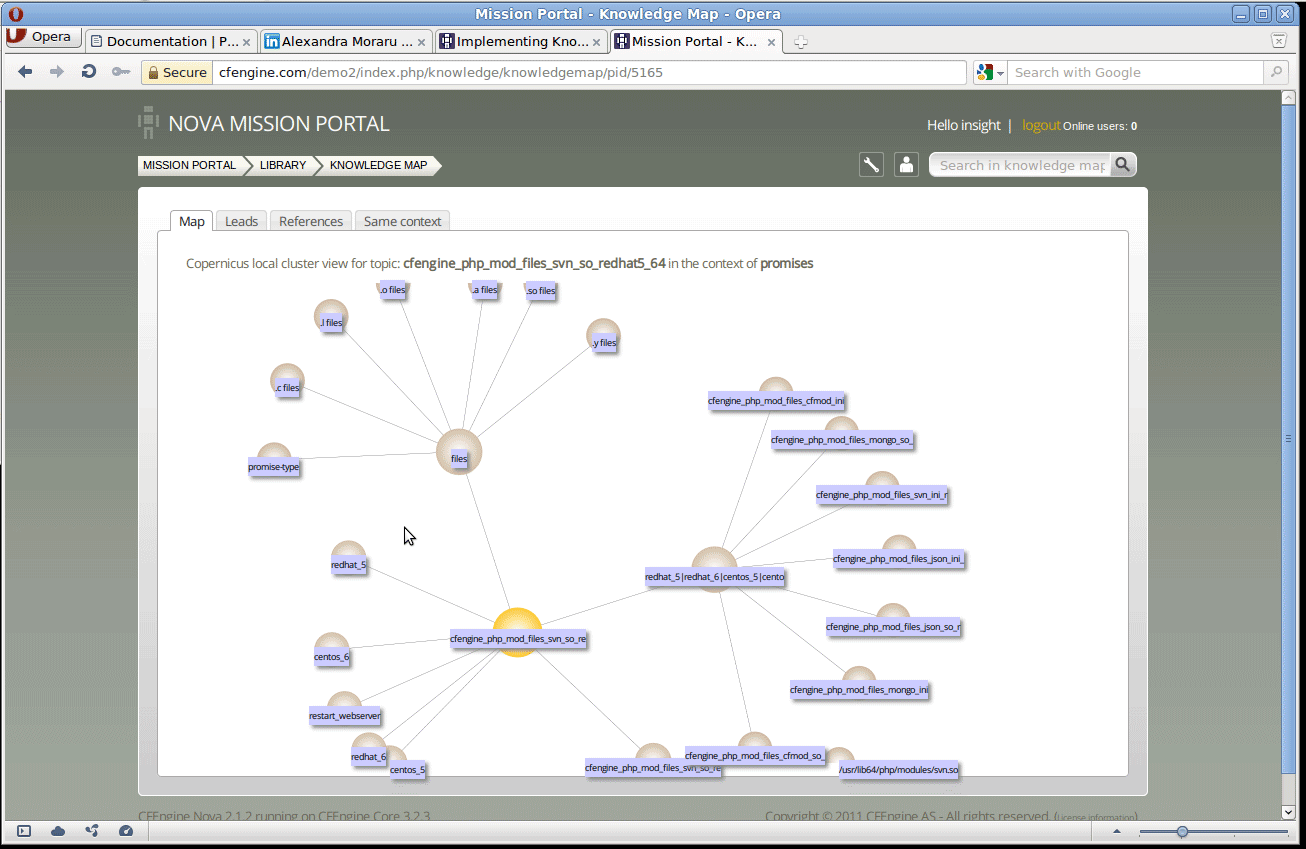

Let's look at the current state of the smart index which we call the (Copernicus) Knowledge Map. If you go to the Mission Portal Library and search for a topic, you will land in the Knowledge Map. You will immediately see a graphical image and number of tabs that contain various different renditions of the information.

Presently, these are called:

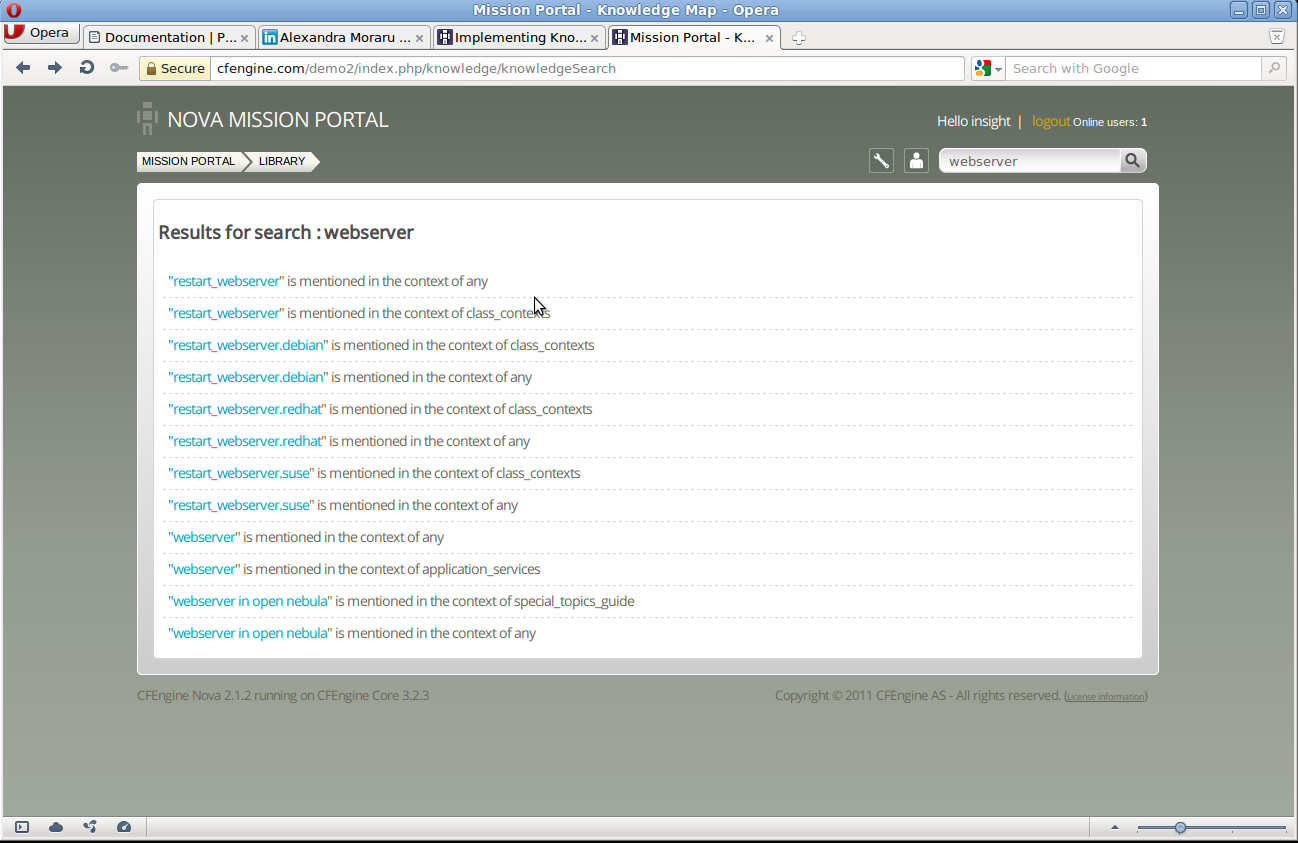

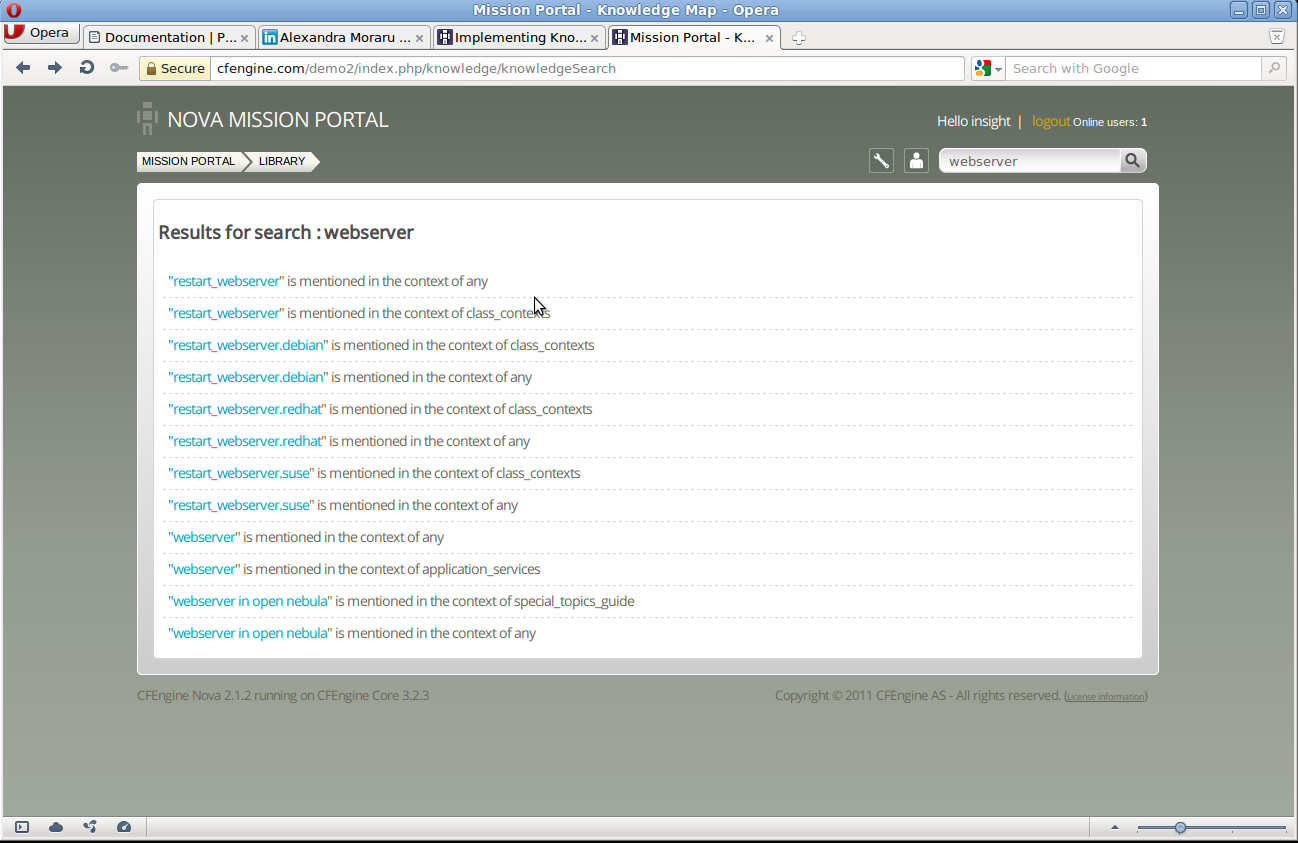

You enter the knowledge map by searching, or being referred there by a link in the Mission Portal. Suppose we enter ‘webserver’ into the search field. CFEngine searches for matching topics in its index, and returns references in different contexts. The context `any' represents an unspecific reference to the topic name:

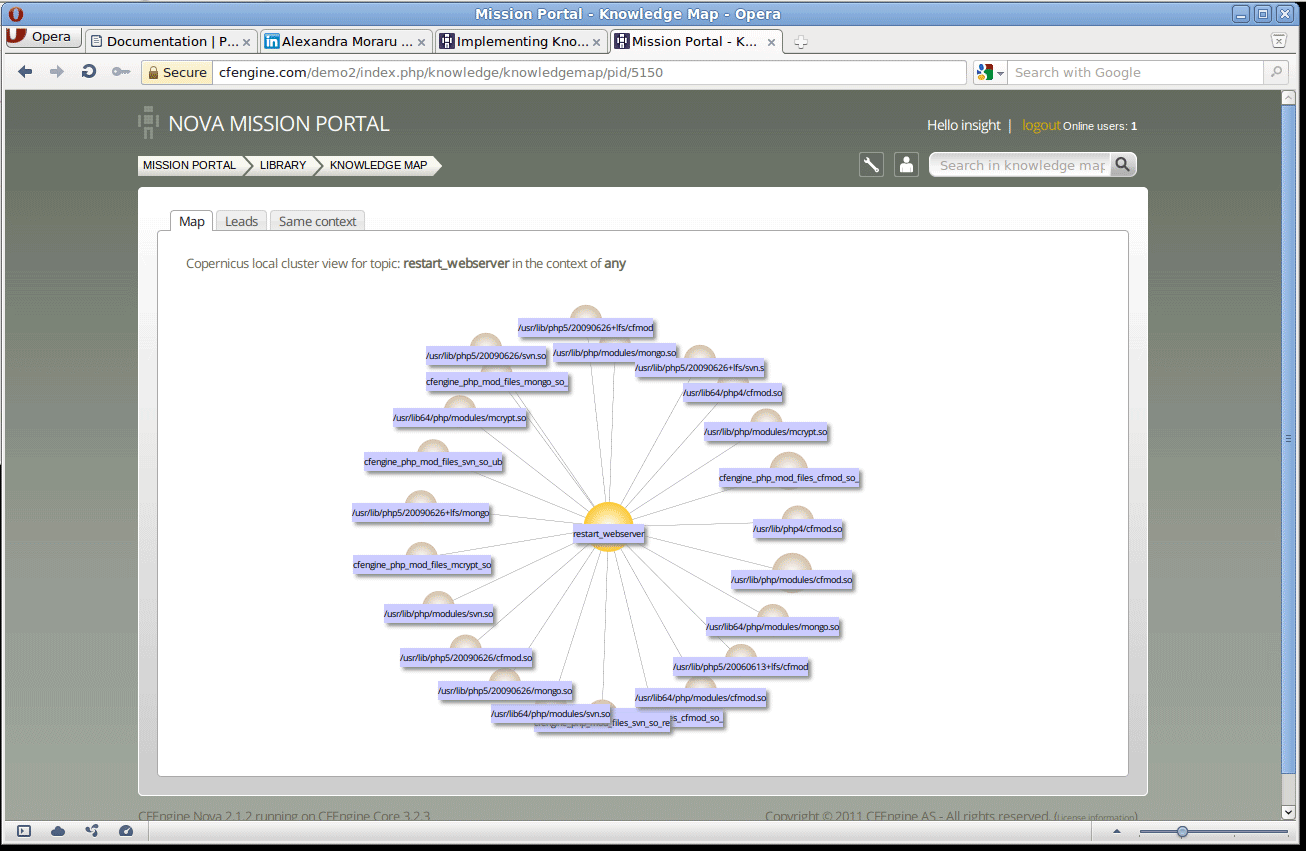

Suppose we click on the first of these in any context; this leads us to a special

landing page about that particular topic which contains the four tabs mentioned above.

By default we end up in the graphical view. This gives an immediate impression of

roughly where CFEngine considers this topic to lie in the scope of its knowledge.

However, its value is rather limited.

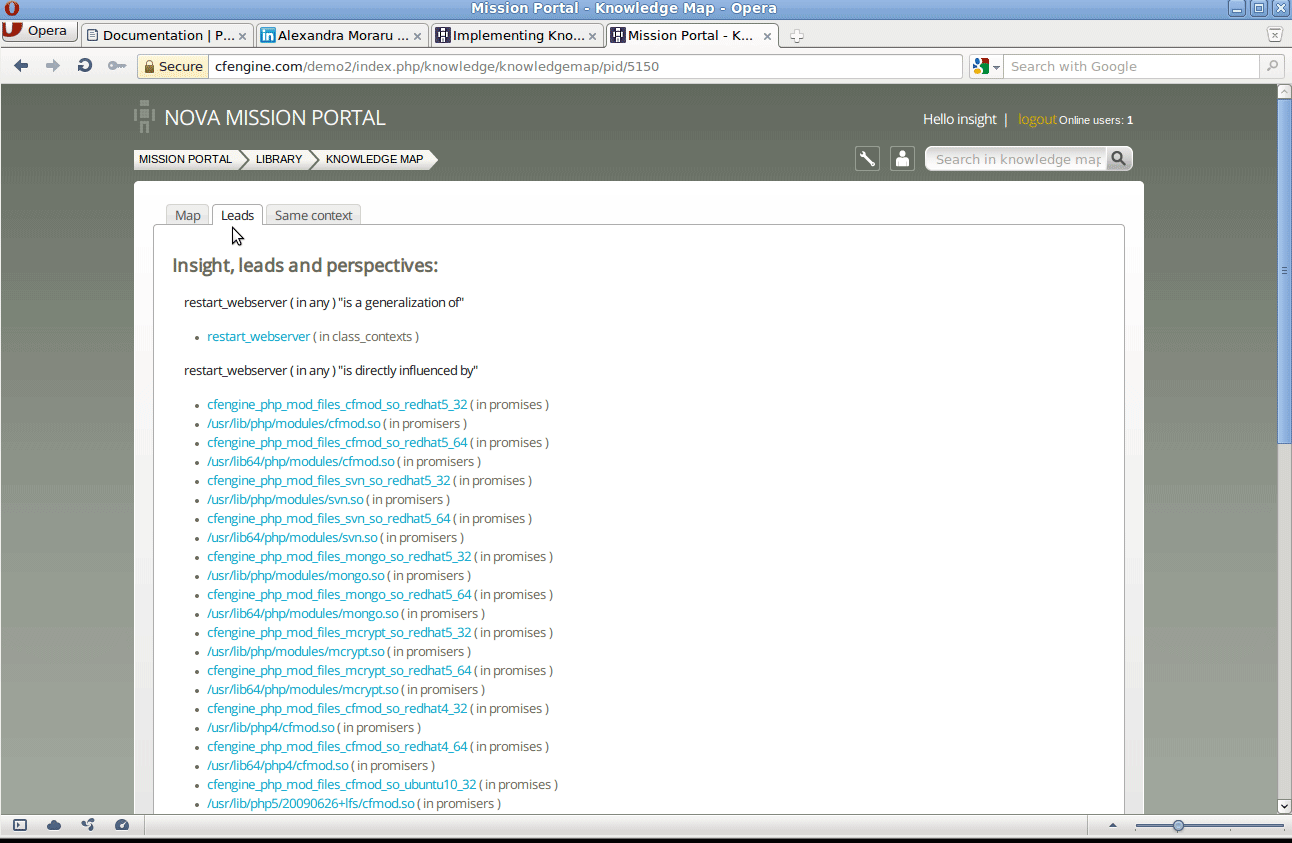

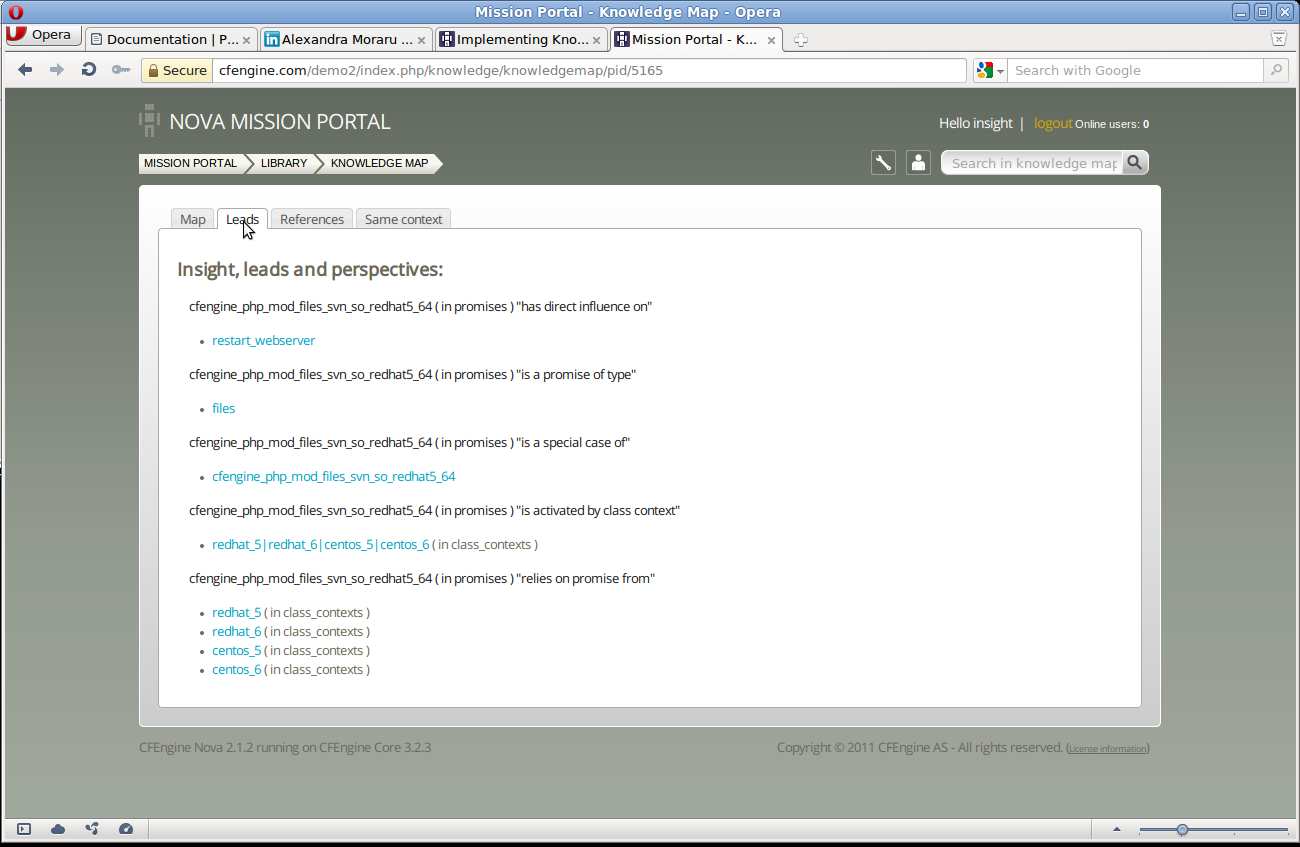

The next step is to walk through the tabs to `drill down' to actual content. The second tab points us to the `brainstorming' value of the associative links – now with explanations in text. If we select another tab we arrive at further leads for assisted thinking: these associative-thinking pointers can guide you to matters that are related and provide context for the current topic.

Leads are helpful if you didn't really know what you were looking for in the first place – and you would like some explanation of what it what you guessed.

If we select one of these, we go the landing page for that new topic in the advertised context.

Note that several topics might be highlighted in yellow on a page – if they have been named, or if they are topics of special importance in this local cluster (meaning that they are highly referred to).

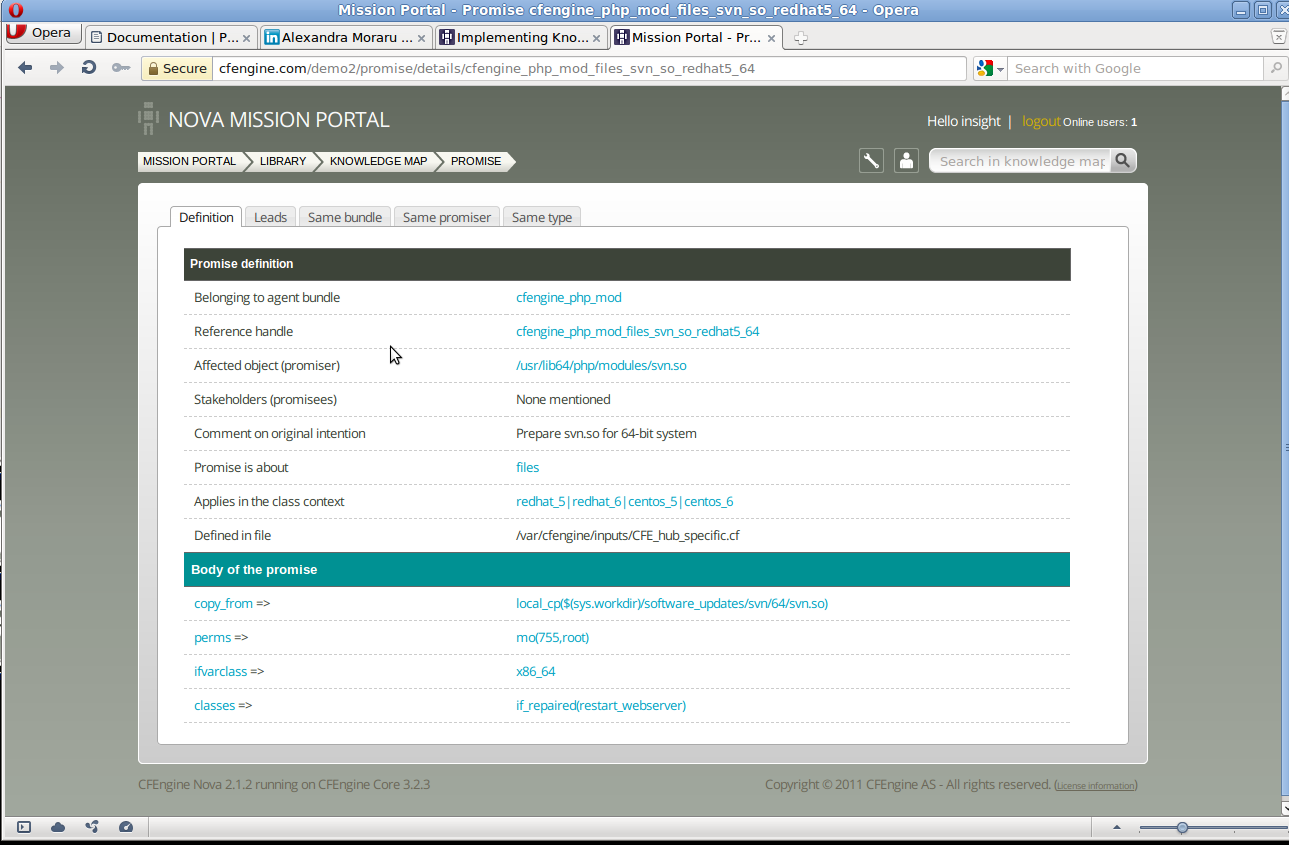

In this view we are able to see, at a glance, that this somewhat Byzantine string is the name of a file, and that is pertains only to certain operating systems. Walking through the tabs again, we see both where we came from and where we can go from here, with more detailed explanations.

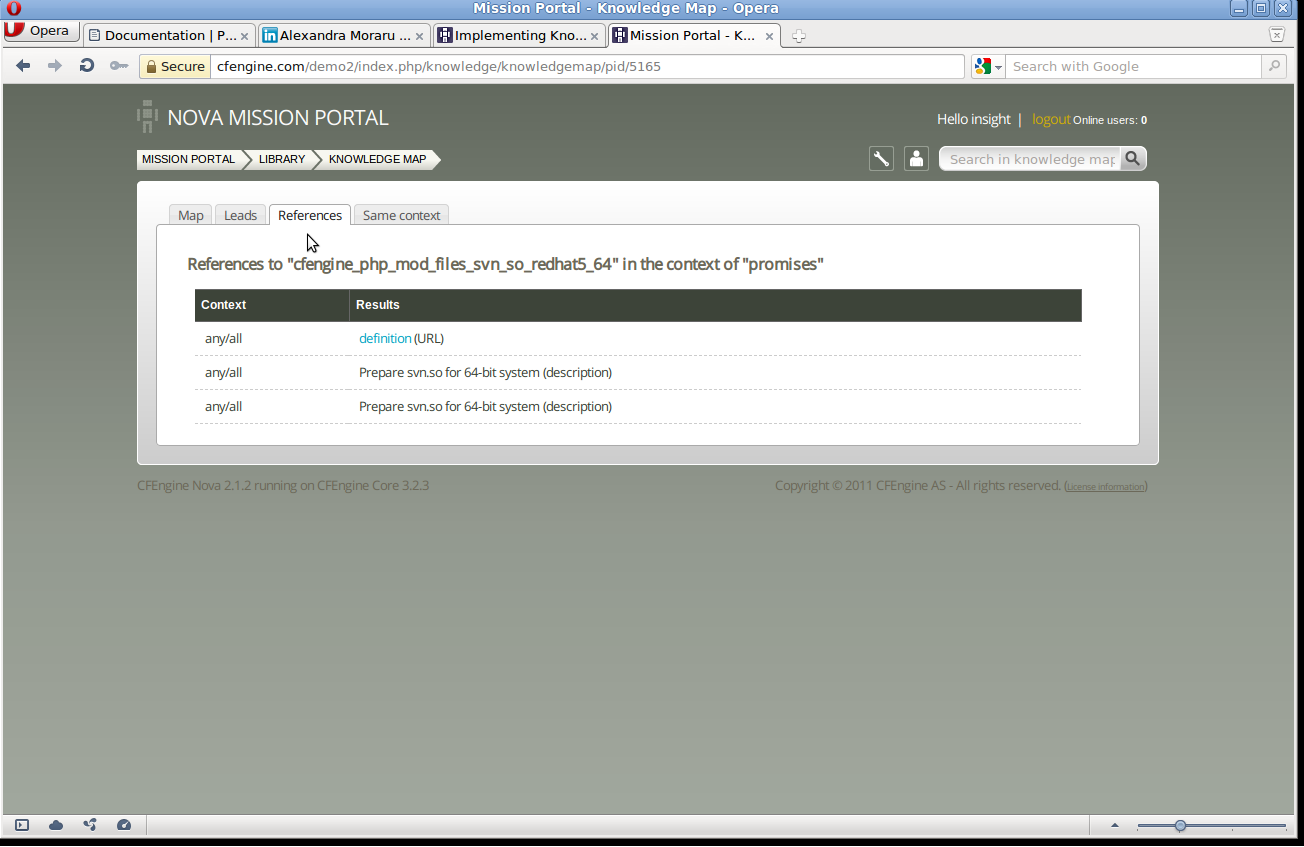

So far the map has only shown us topics – or named subjects categorized by their context. This gives us a kind of compass for knowing what the topic is about, but it tells us little about the subject itself. The third tab points us to actual expansive information about the topic, if any is known. This might be information from the documentation, external links or commentary and remarks made in policy.

| If there are no references to external information, this tab does not appear. Let's choose one of these references; now we are taken to a new topic altogether, where we see a new view of the system information. |

Because the topic name is categorized in the context of `promises', we know that (although this is the name of a file and it refers to RedHat-like operating systems) that this is also the object of a promise. The references page contains a link that then points us to actual information about this promise. The textual comment that was attributed to the promise in the policy itself, and a link to the promise's definiton. Clicking on the defintion link takes us the the promise-viewer.

The Copernicus Knowledge Map view will take you a while to get used to – use it to help you think about matters, and see how they fit together into a systematic overview of your environment.

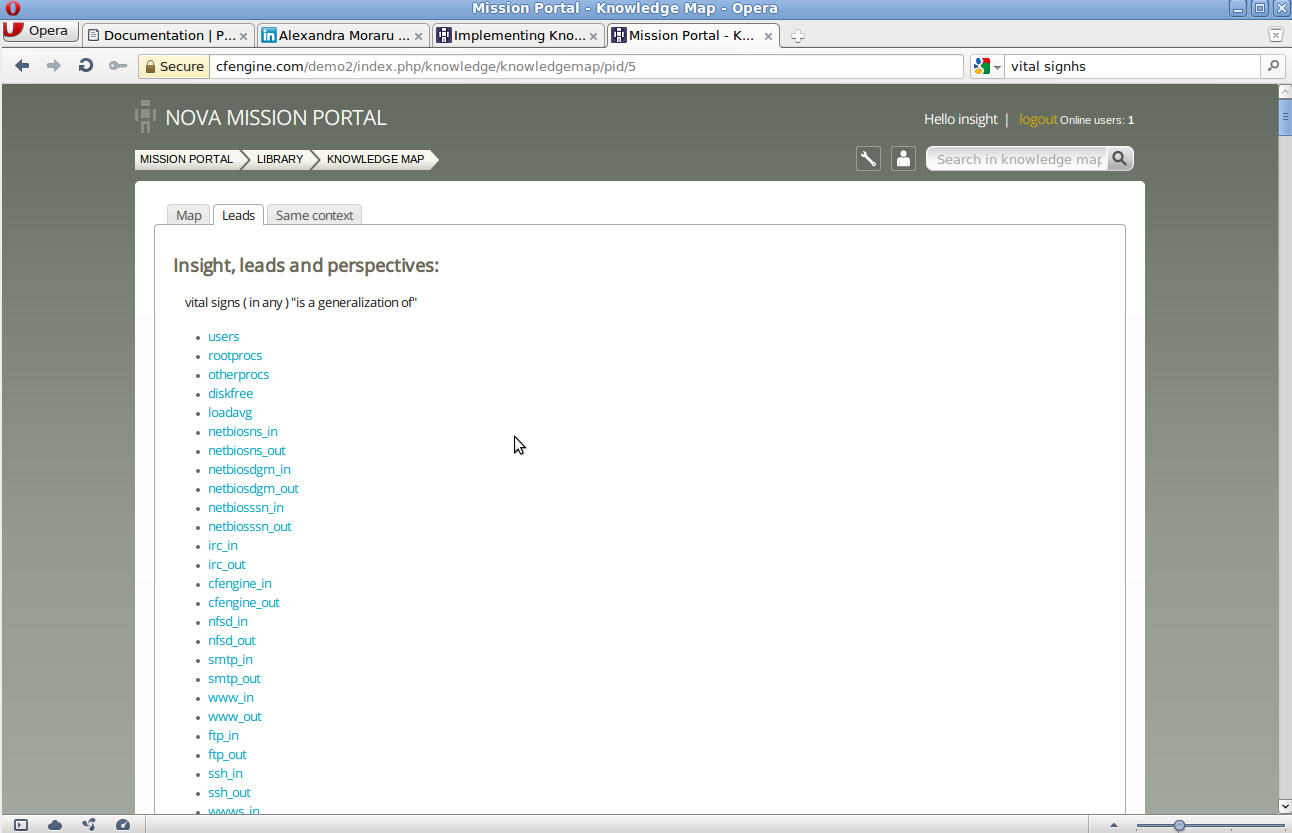

Let's look at another example. Suppose we enter ‘vital signs’ as the search text, and go to the leads. We find a long list of other topics. CFEngine says that `vital signs' generalizes, or is an umbrella concept, for these other concepts.

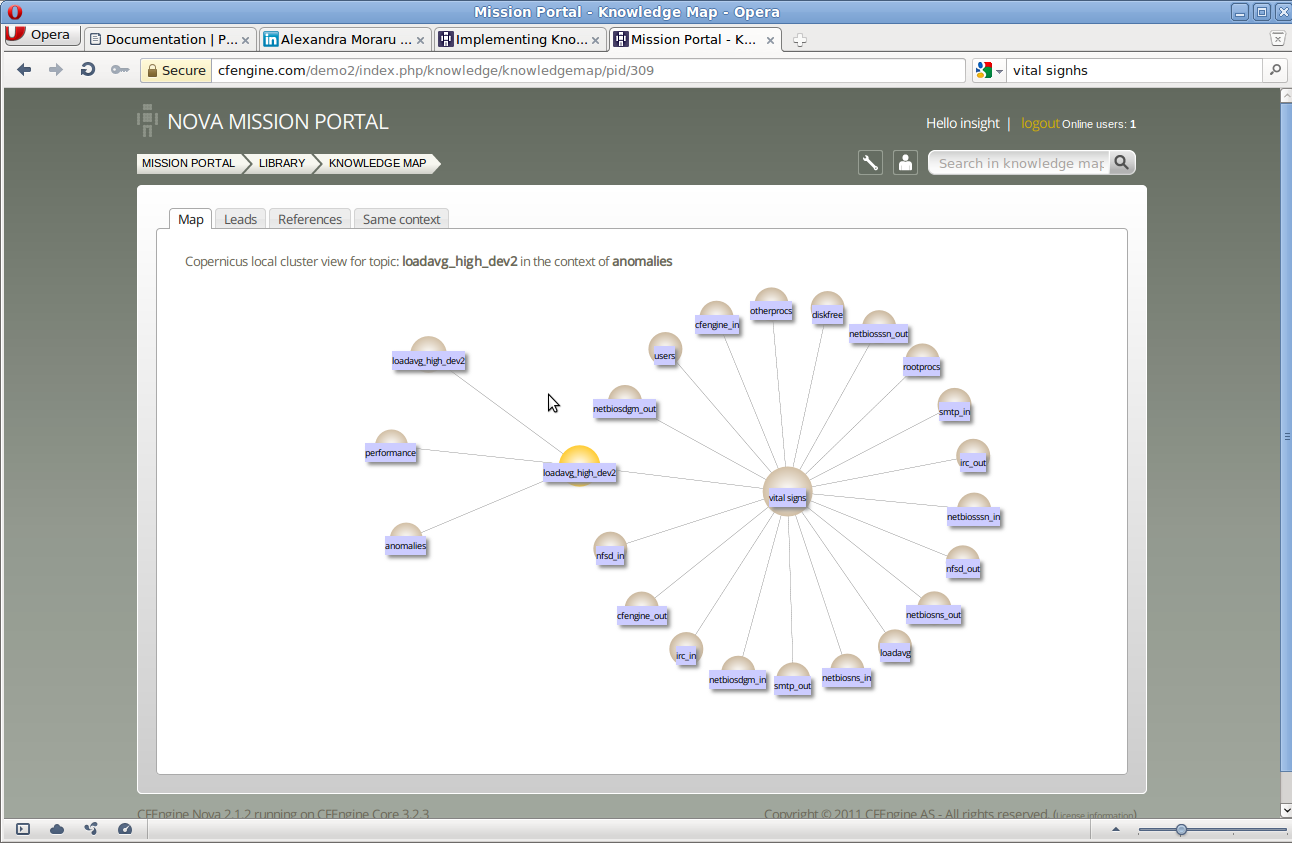

One of these concepts is a class context that represents an anomaly detected by CFEngine ‘loadavg_high_dev2’. Clicking on this, we see the significance of this concept quite easily from its relationship to other concepts:

The load average being high might be an anomaly, but we also see that it refers to system performance, as does a whole bunch of other concepts.

| The value of the semantic indexing is that it is information a casual user can actually learn from. By providing context and leads for further thinking, the Mission Portal becomes an quasi-intelligent assistant for working on the system. |

There are many kinds of information that contribute to a strategy for managing knowledge. The ability to learn from past mistakes demands that we look both forwards and backwards, while realizing that knowledge grows older and less useful the older it gets. For instance, what is known about the past? What is current? How can we track these things? Information comes in logically different categories as well as different types. Data have different sources, and are about different epochs. We need to unify and integrate these in Knowledge Management.

This information comes from the wider culture of the enterprise. It is often

treated poorly as our modern culture has an unreasonable suspicion of anything that

seems `academic'.

This comes from probing and monitoring human-computer processes.

This is closely related to policy and comes from internal management bodies.

Policy is informed by all of the above, and usually changes in response to recurring `problems' identified in the observations. It originates from internal management.

In the foregoing section, we saw how leads in the Knowledge Map's semantic index could help us to see immediate relationships between system issues. The next question is: what about connections that are less immediate or obvious?

In future releases you will be able to ask the agent to brainstorm for you about topics, telling any stories is knows about topics. A story is a simply a path through the web of connected information that follows some kind of connectness. Most interesting stories have a thread of cause and effect. CFEngine attempts to reason forth narratives that might be sensible or which might offer some kind of insight. This is not usually a directly useful revelation, but more often a thought provoking stimulus for a human to take further.

Machine intelligence is never a substitute for the real thing, at least not in our present day technologies, but it can be a useful amplifier of `leads' to get a smart human thinking about the right things. Most CFEngine stories relate to policy, and they are generated automatically by the knowledge engine, so you will not get any stories until you have something interesting in your policy.

Stories will be usable from the command-line, or as a tab within the Mission Portal. The command line is useful for interactive thinking:

A story can be quite simple:

atlas$ src/cf-know --tell-me-about ftpusers

F: "ftpusers" seems to affect "any::/etc/ftpusers" (with 50 % probability)

"ftpusers" (in any),

see also "/etc/ftpusers" (in any),

|

cf-know --tell-me-about anomalies::cpu0_high_dev2

F: "anomalies::cpu0_high_dev2"

seems to affect "any::performance" (with 100 % probability)

"cpu0_high_dev2" (in anomalies),

is a special case of "vital signs" (in any),

which is a generalization of "users_high_dev1" (in anomalies),

and this (users_high_dev1) is a special case of "performance" (in any)

(Note also that performance, which was mentioned, is a generalization of

"anomalies::users_high_dev1")

|

Stories can also be quite spurious, because knowledge itself can be spurious. For instance, some guesses might be quite wrong as the system gets the wrong end of the stick, so to speak, as it uses general patterns and these patterns always have exceptions:

atlas$ src/cf-know --tell-me-about operating_systems::suse

F: "operating_systems::suse" seems to affect "any::gnu/linux" (with 100 % probability)

"suse" (in operating_systems),

is a special case of "linux" (in any),

and this (linux) seems to refer to "gnu/linux" (in any)

F: "operating_systems::suse" seems to affect "any::unitedlinux" (with 100 % probability)

"suse" (in operating_systems),

is a special case of "linux" (in any),

and this (linux) seems to refer to "unitedlinux" (in any)

|

atlas$ src/cf-know --tell-me-about functions

F: "any::functions" seems to affect "any::arrays" (with 100 % probability)

"functions" (in any),

seems to refer to "functions which read" (in any),

which seems to refer to "functions which read arrays" (in any),

and this (functions which read arrays) seems to be referred to in "arrays" (in any)

F: "any::functions" seems to affect "any::expression" (with 100 % probability)

"functions" (in any),

seems to refer to "functions which read" (in any),

which seems to refer to "functions which read classes" (in any),

which seems to be referred to in "class" (in data_types),

which seems to refer to "a cfengine class expression" (in any),

and this (a cfengine class expression) seems to be referred to in "expression"

(in any)

...

|

As you can see, the story generator looks for causative connections between the things that it knows about. Some topics are from the documentation, and some from your configuration policy.

F: "any::functions" seems to affect "any::readrealarray" (with 100 % probability)

"functions" (in any),

seems to refer to "functions which read" (in any),

which seems to be referred to in "class" (in data_types),

which seems to be referred to in "functions which return" (in any),

which seems to refer to "functions which return real" (in any),

which seems to be referred to in "real" (in vars_promises),

and this (real) seems to refer to "readrealarray" (in any)

(Note also that readrealarray, which was mentioned, seems to refer to

"any::functions which read classes")

(Note also that readrealarray, which was mentioned, seems to refer to

"any::functions which return class")

|

CFEngine provides a lot of knowledge about your system out of the box, that includes a domain model about the space of IT management, and an automated analysis of the deployed policy. Below are some notes about how this is built, and things you can do to improve the information by adding knowledge that cannot be discovered automatically.

classes: promises. You should then collect

such classes into a topic context called ‘locations::’ in the company_knowledge.cf file.

cf-promises -r to build a decompsition of your

current policy.

cf-know -bf enterprise_build.cf to build the knowledge map.

Business goals are shown in the Goals app (and service catalogue) in the Mission Portal of CFEngine Enterprise for each hub. To document the fact that a promise or bundle contributes to a business goal, you must do two things:

topics:

goals::

"goal 1" comment => "Do good things";

"goal 2" comment => "Be first";

"goal 3" comment => "Be best";

methods:

"security" -> { goal_1, goal_2 }

comment => "Basic change management",

usebundle => change_management;

"maintenance"

comment => "Perform log rotation",

usebundle => garbage_collection;

To document the location of a host, make sure that it is placed inside a class that represents its address:

classes:

"london" or => { "host1", "host2" };

"alexandria" or => { "host3", "host4", "host5" };

Then designate these classes as locations in the knowledge map:

topics: locations:: "london" comment => "29 Market Street, London XW4, third on the left"; "alexandria" comment => "Secret chamber, discovered by Indiana Jones";

bundle knowledge company_knowledge

{

things:

regions::

"Americas" comment => "USA, Latin America and Canada";

"EMEA" comment => "Europe, The Middle-East and Africa";

"APAC" comment => "Asia and the Pacific countries";

countries::

"USA";

"Germany";

"UK" synonyms => { "Great Britain" },

is_located_in => { "EMEA", "Europe" };

"Netherlands" synonyms => { "Holland" },

is_located_in => { "EMEA", "Europe" };

"Singapore" is_located_in => { "APAC", "Asia" };

site_locations::

# Use this for the names of

"London_1" is_located_in => { "London", "UK" };

"New_Jersey" is_located_in => { "USA" };

routers::

"oslo-hub-p6 " comment => "Cisco xyz router, 3rd floor machine room, 6 Penny Street";

"oslo-hub-trunk" comment => "Cisco BGP router, floor machine room";

"nyc-hub-456" comment => "Juniper 123 router, 3rd floor machine room";

networks::

"192.23.45.0/24"

comment => "Secure network, zone 0. Single octet for corporate offices",

is_connected_to => { "oslo-hub-123" };

"192.12.74.0/23" comment => "Zone 1, double octet for the London office developer network",

is_connected_to => { "oslo-hub-123" };

"192.12.74.0/23"

comment => "Secure, single octet for the NYC office",

is_connected_to => { "nyc-hub-456" };

#######

topics:

company::

"ED" comment => "Exceptional Devices Ltd";

ED::

"EGC" comment => "Enterprise grid computing",

association => a("develops stuff within",

"ED",

"contains its engineering unit");

"EBC" comment => "Enterprise business computing",

association => a("handles business services within",

"ED",

"contains its business unit");

"ED terminology" comment => "Internal company nomenclature";

ED_terminology::

"interactive job" comment => "Interactive software running in the grid";

"apps" comment => "Software applications",

association => a("are also referred to as",

"interactive jobs",

"are also referred to as");

"business services" comment => "Support services for sales";

########################

# GOALS as topics

########################

goals::

"goal 1" comment => "The company mission depends on reliability to our customers";

"goal 2" comment => "Should be running recent versions of key software";

"goal 3" comment => "The company must be compliant with Sarbanes Oxley act.";

"goal 4" comment => "Comply with US Export restrictions for class D countries";

#######

# Documents below

#######

occurrences:

# Fill in company references here

work_shifts::

"http://www.example.com/shifts_and_rotas.ods"

represents => { "Spreadsheet" };

current_projects::

"http://www.example.com/scope_of_work.html"

represents => { "SOW" };

software_licenses::

"This CFEngine software license expires <b>$(sys.expires)</b>"

representation => "literal",

represents => { "CFEngine Nova" };

}

CFEngine cannot produce everything you need for your library of knowledge. There cannot be hard and fast rules about this. Here are some suggestions:

| Hint: a simple way to have a log is to use a tickets system like OTRS or a moderated mailing list, and to email new entries. Something like a Mailman archive allows then tracking and integration. |

Passing on knowledge to others could be considered a `best practice'. Alas, this is not as easy as it sounds. There are plenty of strategies to achieve knowledge transfer:

These are just a few. However, this list is old news, and these items alone will not lead to knowledge transfer.

One of the most important barriers to knowledge transfer is that individuals refuse to learn new things. A lack of dynamism in a company or organization establishes patterns of habit that are hard to break. The longer they last, the more likely they are to continue.

Promise theory makes clear that, even if all staff promise to write excellent documentation, they do not necessarily promise to read each others' documents. Transfer requires a commitment both to send and to receive.

|

Communication skills are clearly important, but this is a serious flaw in the idea. Written communication skills are not as common as we might think. This means it is hard for the writer, and also for the reader.

The solution taken by CFEngine is to reduce the problem of documentation to one of coding notes and relationships. This requires only minor writing skills. The technology can then assemble these notes using intelligent algorithms and present the result in an organized form with visual aids. You should pay special attention to the syntax items:

comment =>

handle =>

depends_on =>

-> { promisees }

You need to foster a culture of using information, in order for it to become assimilated as knowledge. Unused information will perish.

As a manifesto for us as developers at CFEngine, as well as for you as users of the software, and as infrastructure engineers, it is helpful to make a list of questions that we would like to be able to answer using enterprise software. The following list is not to be regarded as a set of features in CFEngine, but rather as a set of challenges to be addressed in different ways.

[1] This is a general statement of the second law of

thermodynamics – entropy tends to increase. If we want to reduce it

locally, we have to expend a lot of effort.

Table of Contents

Footnotes